Critical Care

The Southwest Journal of Pulmonary and Critical Care publishes articles directed to those who treat patients in the ICU, CCU and SICU including chest physicians, surgeons, pediatricians, pharmacists/pharmacologists, anesthesiologists, critical care nurses, and other healthcare professionals. Manuscripts may be either basic or clinical original investigations or review articles. Potential authors of review articles are encouraged to contact the editors before submission, however, unsolicited review articles will be considered.

Point-of-Care Ultrasound and Right Ventricular Strain: Utility in the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Embolism

Ramzi Ibrahim MD, João Paulo Ferreira MD

Department of Medicine, University of Arizona – Tucson and Banner University Medical Center

Tucson AZ USA

Abstract

Pulmonary emboli are associated with high morbidity and mortality, prompting early diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Utilization of rapid point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) to assess for signs of pulmonary emboli can provide valuable information to support immediate treatment. We present a case of suspected pulmonary embolism in the setting of pharmacological prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism with identification of right heart strain on bedside POCUS exam. Early treatment with anticoagulation was initiated considering the clinical presentation and POCUS findings. CT angiogram of the chest revealed bilateral pulmonary emboli, confirming our suspicion. Utilizing POCUS in a case of suspected pulmonary emboli can aid in clinical decision making.

Case Presentation

Our patient is a 50-year-old man with a history of morbid obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, and poorly controlled diabetes mellitus type 2 who was admitted to the hospital for sepsis secondary to left foot cellulitis and found to have left foot osteomyelitis with necrosis of the calcaneus. The patient was started on intravenous antimicrobials, underwent incision and debridement, and completed a partial calcanectomy of the left foot. During the hospital course, he remained on subcutaneous unfractionated heparin at 7,500 units three times a day for prevention of deep vein thrombosis. On post-operative day 12, he developed acute onset of dyspnea requiring 2 liters of supplemental oxygen and was slightly tachycardic in the low 100s. He complained of chest tightness without pain, however, he denied lower extremity discomfort, palpitations, orthopnea, or diaphoresis. Electrocardiogram was remarkable for sinus tachycardia without significant ST changes, T-wave inversions, conduction defects, or QTc prolongation. Rapid point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) at bedside revealed interventricular septal bowing, hypokinesia of the mid free right ventricular wall, and increased right ventricle to left ventricle size ratio (>1:1 respectively) (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. A: Static apical 4-chamber view showing interventricular bowing into the left ventricle (blue arrow), significantly enlarged right ventricle, and right ventricular free wall hypokinesia (green arrow). B: Video of apical 4-chamber view.

Figure 1. A: Static apical 4-chamber view showing interventricular bowing into the left ventricle (blue arrow), significantly enlarged right ventricle, and right ventricular free wall hypokinesia (green arrow). B: Video of apical 4-chamber view.

Figure 2. A: Static parasternal short axis view showing interventricular septal bowing in the left ventricle (green arrow). B: Video of parasternal short axis view.

Figure 2. A: Static parasternal short axis view showing interventricular septal bowing in the left ventricle (green arrow). B: Video of parasternal short axis view.

With these findings, the patient was started on therapeutic anticoagulation. CT angiogram of the chest revealed a large burden of bilateral pulmonary emboli (PE). The pulmonary embolism severity index (PESI) score was 130 points which is associated with a 10%-24.5% mortality rate in the following 30 days. Formal echocardiogram showed a severely dilated right ventricle with reduced systolic function, paradoxical septal movement, and a D-shaped left ventricle. Patient remained hemodynamically stable and was discharged home after transition from heparin to rivaroxaban.

Discussion

Pulmonary emboli remain a commonly encountered pathological phenomenon in the hospital setting with a mortality rate ranging from <5% to 50% (1). Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis has been shown to reduce the risk of VTE in hospitalized patients, however, this does not eliminate the risk completely. Prompt diagnosis allows earlier treatment and improved outcomes however this is often challenging given the lack of specificity associated with its characteristic clinical symptoms (2). In the proper context, utilization of POCUS can aid the diagnosis of PE by assessing for signs of right ventricular strain. Characteristic findings seen on a cardiac-focused POCUS that represent right ventricular strain include McConnell’s sign (defined as right ventricular free wall akinesis/hypokinesis with sparing of the apex), septal flattening, right ventricular enlargement, tricuspid regurgitation, and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion under 1.6 cm (3). Their respective sensitivities and specificities are highly dependent on the pre-test probability. For example, a prospective cohort study completed by Daley et al. (4) in 2019 showed that for patients with a clinical suspicion of PE, sensitivity of right ventricular strain was 100% for a PE in patients with a heart rate (HR) >110 beats per minute, and a sensitivity of 92% if HR >100 BPM. This study provides evidence to support the use of cardiac focused POCUS in ruling out pulmonary emboli in patients with signs of right ventricular strain and abnormal hemodynamic parameters such as tachycardia. Additionally, in settings where hemodynamic instability is present and the patient cannot be taken to the CT scanner for fear of decompensation, rapid POCUS assessment can be helpful. In our patient, given the acute need for supplemental oxygenation and dyspnea, along with his risk factors for a thromboembolic event, the use of POCUS aided in our clinical decision making. The yield of information that can be provided by POCUS is vital for early diagnostic and therapeutic decision making for patients with a clinical suspicion of pulmonary emboli.

References

- Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2008 Sep;29(18):2276-315. [CrossRef][PubMed]

- Roy PM, Meyer G, Vielle B, et al. Appropriateness of diagnostic management and outcomes of suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. 2006 Feb 7;144(3):157-64. [CrossRef][PubMed]

- Alerhand S, Sundaram T, Gottlieb M. What are the echocardiographic findings of acute right ventricular strain that suggest pulmonary embolism? Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2021 Apr;40(2):100852. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daley JI, Dwyer KH, Grunwald Z, et al. Increased Sensitivity of Focused Cardiac Ultrasound for Pulmonary Embolism in Emergency Department Patients With Abnormal Vital Signs. Acad Emerg Med. 2019 Nov;26(11):1211-1220. [CrossRef][PubMed]

Cite as: Ibrahim R, Ferreira JP. Point-of-Care Ultrasound and Right Ventricular Strain: Utility in the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Embolism. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care Sleep. 2022;25(2):34-36. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpccs040-22 PDF

Point of Care Ultrasound Utility in the Setting of Chest Pain: A Case of Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy

Ramzi Ibrahim MD, Chelsea Takamatsu MD, João Paulo Ferreira MD

Department of Medicine, University of Arizona - Tucson and Banner University MedicalCenter, Tucson

Tucson, AZ USA

Abstract

Chest pain is a frequently encountered chief complaint in the Emergency Department and entails a broad differential. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) can be utilized to guide diagnostic decision making and initial triaging. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy presents similarly to acute coronary syndrome and has characteristic findings on echocardiogram. This case presentation details a scenario of ST segment elevation on electrocardiogram and elevated high sensitivity troponin levels, worrisome for a ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Apical hypokinesis to akinesis and apical ballooning were appreciated on echocardiogram, raising suspicion for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, subsequently confirmed by coronary angiogram. A cardiac focused point-of-care ultrasound assessment can provide valuable information to aid in diagnostic accuracy.

Case Presentation

A 72-year-old woman with a known history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) presented to the hospital for progressively worsening dyspnea in the previous few days along with new onset chest discomfort in the past one day. Patient was found to have an oxygen saturation of 87% on room air, pH of 7.25 and a pCO2 of 98 on venous blood gas, and was admitted for acute on chronic hypoxic and hypercapnic respiratory failure in the setting of a COPD exacerbation. Patient was intubated for respiratory distress and worsening acuteencephalopathy. Chest radiograph was grossly unremarkable for consolidations or

opacities. A bedside point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) assessment revealed clear lung zones bilaterally without apparent B lines; however, minimal pleural sliding was appreciated on the left anterior lung zones. Cardiac focused assessment identified marked hypokinesis to akinesis of the entire mid-distal left ventricle with apical ballooning, raising the suspicion of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (Videos 1-2).

Video 1. Subcostal view with identification of a hyperkinetic basal segment and hypokinetic apex. Apical ballooning is also clearly identifiable in this view. (Click here to view the video in a separate window)

Video 2. Parasternal short axis identifying a hyperkinetic basal segment near the level of the mitral valve with subsequent hypokinetic apical view. The image plane is being panned from base to apex and back. (Click here to view the video in a separate window).

High sensitivity troponin level was elevated at 42 ng/L with an increase to 540 ng/L on repeat testing. Electrocardiogram (ECG) was initially grossly unremarkable for signs of acute ischemic changes, however, repeat ECG revealed ST elevation in the anterior leads. The patient was taken urgently to the catheterization lab where intervention identified mild non-obstructive disease in a right dominant circulation and the diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy was confirmed.

Discussion

Chest pain is among the most common chief complaints of patients presenting to the Emergency Department. The differential diagnoses of chest pain remain broad which includes a variety of pathological processes. POCUS has emerged as an indispensable tool for diagnostic accuracy and for aid with initial triaging before considering further confirmatory testing. An emerging consideration is its utility in the acute setting, specifically when trying to differentiate between cardiac and non-cardiac chest pain. Comprehensive echocardiography, usually completed in a formal setting upon request, provides valuable information that can be indicative of ischemic states, including regional wall motion abnormalities, decreased systolic movement, decreased myocardial thickening, valvular function abnormalities, inter-ventricular shunts, and acute papillary muscle dysfunction (1). Alternatively, bedside POCUS in acute settings for assessment of cardiac function and structural abnormalities provides timely objective data but holds greater limitations mainly due to inferior ultrasound quality, variable operator skillsets, and time constraints. of

In our case, we utilized POCUS in an unresponsive, intubated patient, noting discrete regions of hypokinesis-akinesis the left ventricle with apical ballooning, prior to ECG showing elevated ST segments in the anterior leads and a rising troponin level on serial lab tests. Our initial impression based on the POCUS findings was concerning for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Given the urgency of the troponin and ECG abnormalities, a Code STEMI was called. Cardiology urgently took the patient to the catheterization lab which confirmed the diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy after identifying no obstructive coronary artery disease.

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy often presents very similarly to acute coronary syndrome with elevated markers of myocardial ischemia and ST changes on ECG (2). Hallmarks of this clinical entity include apical hypokinesia and basal segment hyperkinesia on echocardiogram and no obstructive coronary artery disease on coronary angiography. Given the acuity of these findings, this case presentation portrays the importance of utilizing a cardiac focused POCUS assessment to help tailor differential diagnoses and raise index of suspicion not only to acute coronary syndromes, but also to mimicking clinical diseases.

References

- Leischik R, Dworrak B, Sanchis-Gomar F, Lucia A, Buck T, Erbel R. Echocardiographic assessment of myocardial ischemia. Ann Transl Med. 2016 Jul;4(13):259. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad A, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Apical ballooning syndrome (Tako-Tsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): a mimic of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2008 Mar;155(3):408-17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Sometimes It’s Better to Be Lucky than Smart

Robert A. Raschke MD and Randy Weisman MD

Critical Care Medicine

HonorHealth Scottsdale Osborn Medical Center

Scottsdale, AZ USA

We recently responded to a code arrest alert in the rehabilitation ward of our hospital. The patient was a 47-year-old man who experienced nausea and diaphoresis during physical therapy. Shortly after the therapists helped him sit down in bed, he became unconsciousness and pulseless. The initial code rhythm was a narrow-complex pulseless electrical activity (PEA). He was intubated, received three rounds of epinephrine during approximately 10 minutes of ACLS/CPR before return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), and was subsequently transferred to the ICU.

Shortly after arriving, a 12-lead EKG was performed (Figure 1), and PEA recurred.

Figure 1. EKG performed just prior to second cardiopulmonary arrest showing S1 Q3 T3 pattern (arrows).

Approximately ten-minutes into this second episode of ACLS, a cardiology consultant informed the code team of an S1,Q3,T3 pattern on the EKG. A point-of-care (POC) echocardiogram performed during rhythm checks was technically-limited, but showed a dilated hypokinetic right ventricle (see video 1).

Video 1. Echocardiogram performed during ACLS rhythm check: Four-chamber view is poor quality, but shows massive RV dilation and systolic dysfunction.

Approximately twenty-minutes into the arrest, 50mg tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) was administered, and return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) achieved two minutes later. A tPA infusion was started. The patient’s chart was reviewed. He had received care in our ICU previously, but this wasn’t immediately recognized because he had subsequently changed his name of record to the pseudonym “John Doe” (not the real pseduonym), creating two separate and distinct EMR records for the single current hospital stay. Review of the first of these two records, identified by his legal name, revealed he had been admitted to our ICU one month previously for a 5.4 x 3.6 x 2.9 cm left basal ganglia hemorrhage. We stopped the tPA infusion.

On further review of his original EMR is was noted that two weeks after admission for intracranial hemorrhage, (and two weeks prior to cardiopulmonary arrest), he had experienced right leg swelling and an ultrasound demonstrated extensive DVT of the right superficial femoral, saphenous, popliteal and peroneal veins. An IVC filter had been due to anticoagulant contraindication. The patient’s subsequent rehabilitation had been progressing well over the subsequent two weeks and discharge was being discussed on the day cardiopulmonary arrest occurred.

On post-arrest neurological examination, the patient gave a left-sided, thumbs-up to verbal request. Ongoing hypotension was treated with a norepinephrine infusion and inhaled epoprostenol. An emergent head CT was performed and compared to a head CT from four weeks previously (Figure 2), showing normal evolution of the previous intracranial hemorrhage without any new bleeding.

Figure 2. CT brain four weeks prior to (Panel A), and immediately after cardiopulmonary arrest and administration of tPA (Panel B), showing substantial resolution of the previous intracranial hemorrhage.

A therapeutic-dose heparin infusion was started. An official echo confirmed the findings of our POC echo performed during the code, with the additional finding of McConnell’s sign. McConnell’s sign is a distinct echocardiographic finding described in patients with acute pulmonary embolism with regional pattern of right ventricular dysfunction, with akinesia of the mid free wall but normal motion at the apex (1). A CT angiogram showed bilateral pulmonary emboli, and interventional radiology performed bilateral thrombectomies. Hypotension resolved immediately thereafter. The patient was transferred out of the ICU a few days later and resumed his rehabilitation.

A few points of interest:

- IVC filters do not absolutely prevent life-threatening pulmonary embolism (2,3).

- Sometimes, serendipity smiles, as when the cardiologist happened into the room during the code, and provided an essential bit of information.

- Emergent POC ultrasonography is an essential tool in the management of PEA arrest of uncertain etiology.

- Barriers to access of prior medical records can lead to poorly-informed decisions. But in this case, ignorance likely helped us make the right decision.

- Giving lytic therapy one month after an intracranial hemorrhage is not absolutely contra-indicated when in dire need.

- As the late great intensivist, Jay Blum MD used to say: “Sometimes it’s better to be lucky than smart.”

References

- Ogbonnah U, Tawil I, Wray TC, Boivin M. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: Caught in the act. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;17(1):36-8. [CrossRef]

-

Urban MK, Jules-Elysee K, MacKenzie CR. Pulmonary embolism after IVC filter. HSS J. 2008 Feb;4(1):74-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

PREPIC Study Group. Eight-year follow-up of patients with permanent vena cava filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism: the PREPIC (Prevention du Risque d'Embolie Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave) randomized study. Circulation. 2005 Jul 19;112(3):416-22. doi: [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Raschke RA, Weisman R. Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Sometimes It’s Better to Be Lucky than Smart. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2021;22(6):116-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc016-21 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: An Unexpected Target Lesion

Jantsen Smith, MD

Department of Internal Medicine

University of New Mexico Hospital

Albuquerque, NM USA

A 39-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital for shortness of breath. Her medical history was significant for human immunodeficiency virus infection (not on anti-retroviral therapy), superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome with history of SVC stenting, cerebrovascular accident complicated by seizure disorder and swallowing difficulties, moderate pulmonary hypertension, end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis with past episodes of acute hypoxic respiratory failure related to fluid overload. Shortly after admission, the patient experienced a cardiac arrest due to hypoxia and necessitated emergent intubation. This was presumed to be due to fluid overload. Nephrology was consulted for emergent dialysis (the patient had a right upper extremity fistula for dialysis access). Dialysis was initiated through a right arm fistula. On day three of admission, the patient was noted to have worsening right upper extremity and breast swelling and pain. Physical exam revealed indurated edema of the skin of the breast. Point of care ultrasound was performed of the patient’s right neck, and the following ultrasound was obtained approximately 4cm above the clavicle in the right lateral neck.

Video 1. Ultrasound image of the right neck in the transverse plane.

What is the most likely cause of this patient’s right upper extremity and breast swelling? (Click on the correct answer for an explanation).

- Right breast cellulitis

- Ascending SVC thrombus

- Lymphatic blockage of right axillary nodes

- Fluid overload complicated by third spacing in the R upper extremity

Cite as: Smith J. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: An unexpected target lesion. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2019;18(3):63-4. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc011-19 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Characteristic Findings in A Complicated Effusion

Emilio Perez Power MD, Madhav Chopra MD, Sooraj Kumar MD, Tammy Ojo MD, and James Knepler MD

Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care and Sleep

University of Arizona College of Medicine

Tucson, AZ USA

Case Presentation

A 60-year-old man with right sided invasive Stage IIB squamous lung carcinoma, presented with a one week history of progressively worsening shortness of breath, fever, and chills. On admission, the patient was hemodynamically stable on 5L nasal cannula with an oxygen saturation at 90%. Physical exam was significant for a cachectic male in moderate respiratory distress using accessory muscles but able to speak in full sentences. His pulmonary exam was significant for severely reduced breath sound on the right along with dullness to percussion. His initial laboratory finding showed a mildly elevated WBC count 15.3 K/mm3, which was neutrophil predominant and initial chest x-ray with complete opacification of the right hemithorax. An ultrasound of the right chest was performed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Ultrasound of the right chest, mid axillary line, coronal view.

Based on the ultrasound image shown what is the likely cause of the patient’s opacified right hemithorax?

Cite as: Power EP, Chopra M, Kumar S, Ojo T, Knepler J. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: characteristic findings in a complicated effusion. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;17(6):150-2. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc122-18 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Who Stole My Patient’s Trachea?

Monika Kakol MD, Connor Trymbulak MSc, and Rodrigo Vazquez Guillamet MD

Department of Internal Medicine Department

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

Albuquerque, NM USA

A 73-year-old man with a past medical history of asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome and coronary artery disease presented to the emergency department with acute on chronic respiratory failure. The patient failed to respond to initial bronchodilator treatment and non-invasive positive pressure ventilation. A decision was made to proceed with endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. Upper airway ultrasonography was used to confirm positioning of the endotracheal tube and the following images were obtained:

Figure 1. Longitudinal view of the trachea.

Figure 2. Transverse view of the trachea at the level of the tracheal rings.

What does the ultrasound depict (see Figures 1 & 2)? (Click on the correct answer for an explanation)

Cite as: Kakol M, Trymbulak C, Guillamet RV. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: Who stole my patient’s trachea? Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;17(2):72-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc102-18 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Caught in the Act

Uzoamaka Ogbonnah MD1

Isaac Tawil MD2

Trenton C. Wray MD2

Michel Boivin MD1

1Department of Internal Medicine

2Department of Emergency Medicine

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

Albuquerque, NM USA

A 16-year-old man was brought to the Emergency Department via ambulance after a fall from significant height. On arrival to the trauma bay, the patient was found to be comatose and hypotensive with a blood pressure of 72/41 mm/Hg. He was immediately intubated, started on norepinephrine drip with intermittent dosing of phenylephrine, and transfused with 3 units of packed red blood cells. He was subsequently found to have extensive fractures involving the skull and vertebrae at cervical and thoracic levels, multi-compartmental intracranial hemorrhages and dissection of the right cervical internal carotid and vertebral arteries. He was transferred to the intensive care unit for further management of hypoxic respiratory failure, neurogenic shock and severe traumatic brain injury. Following admission, the patient continued to deteriorate and was ultimately declared brain dead 3 days later. The patient’s family opted to make him an organ donor

On ICU day 4, one day after declaration of brain death, while awaiting organ procurement, the patient suddenly developed sudden onset of hypoxemia and hypotension while being ventilated. The patient had a previous trans-esophageal echo (TEE) the day prior (Video 1). A repeat bedside TEE was performed revealing the following image (Video 2).

Video 1. Mid-esophageal four chamber view of the right and left ventricle PRIOR to onset of hypoxemia.

Video 2. Mid-esophageal four chamber view of the right and left ventricle AFTER deterioration.

What is the cause of the patient’s sudden respiratory deterioration? (Click on the correct answer to be directed to an explanation)

- Atrial Myxoma

- Fat emboli syndrome

- Thrombus in-transit and pulmonary emboli

- Tricuspid valve endocarditis

Cite as: Ogbonnah U, Tawil I, Wray TC, Boivin M. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: Caught in the act. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;17(1):36-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc091-18 PDF

March 2018 Critical Care Case of the Month

Babitha Bijin MD

Jonathan Callaway MD

Janet Campion MD

University of Arizona

Department of Medicine

Tucson, AZ USA

Chief Complaints

- Shortness of breath

- Worsening bilateral LE edema

History of Present Illness

A 53-year-old man with history of multiple myeloma and congestive heart failure presented to the emergency department with complaints of worsening shortness of breath and bilateral lower extremity edema for last 24 hours. In the last week, he has had dyspnea at rest as well as a productive cough with yellow sputum. He describes generalized malaise, loss of appetite, possible fever and notes new bilateral pitting edema below his knees. Per patient, he had flu-like symptoms one week ago and was treated empirically with oseltamivir.

Past Medical History

- Multiple myeloma-IgG kappa with calvarial and humeral metastases, ongoing treatment with cyclophosphamide, bortezomib and dexamethasone

- Community acquired pneumonia 2016, treated with oral antibiotics

- Heart failure with echo 10/2017 showing moderate concentric left ventricular hypertrophy, left ventricular ejection fraction 63%, borderline left atrial and right atrial dilatation, diastolic dysfunction, right ventricular systolic pressure estimated 25 mm Hg

- Hyperlipidemia

- Chronic kidney disease, stage III

Home Medications: Aspirin 81mg daily, atorvastatin 80mg daily, furosemide 10mg daily, calcium / Vitamin D supplement daily, oxycodone 5mg PRN, chemotherapy as above

Allergies: No known drug allergies

Social History:

- Construction worker, not currently working due to recent myeloma diagnosis

- Smoked one pack per day since age 16, recently quit with 30 pack-year history

- Drinks beer socially on weekends

- Married with 3 children

Family History: Mother with hypertension, uncle with multiple myeloma, daughter with rheumatoid arthritis

Review of Systems: Negative except per HPI

Physical Exam

- Vitals: T 39.3º C, BP 80/52, P121, R16, SpO2 93% on 2L

- General: Alert man, mildly dyspneic with speech

- Mouth: Nonicteric, moist oral mucosa, no oral erythema or exudates

- Neck: No cervical neck LAD but JVP to angle of jaw at 45 degrees

- Lungs: Bibasilar crackles with right basilar rhonchi, no wheezing

- Heart: Regular S1 and S2, tachycardic, no appreciable murmur or right ventricular heave

- Abdomen: Soft, normal active bowel sounds, no tendernesses, no hepatosplenomegaly

- Ext: Pitting edema to knees bilaterally, no cyanosis or clubbing, normal muscle bulk

- Neurologic: No focal abnormalities on neurologic exam

Laboratory Evaluation

- Complete blood count: WBC 15.9 (92% neutrophils), Hgb/Hct 8.8/27.1, Platelets 227

- Electrolytes: Na+ 129, K+ 4.0, Cl- 100, CO2 18, blood urea nitrogen 42, creatinine 1.99 (baseline Cr 1.55)

- Liver: AST 35, ALT 46, total bilirubin1.7, alkaline phosphatase 237, total protein 7.4, albumin 2.

- Others: troponin 0.64, brain naturetic peptide 4569, venous lactate 2.6

Chest X-ray

Figure 1. Admission chest x-ray.

Thoracic CT (2 views)

Figure 2. Representative images from the thoracic CT scan in lung windows.

What is most likely etiology of CXR and thoracic CT findings? (Click on the correct answer to proceed to the second of seven pages)

- Coccidioidomycosis pneumonia

- Pulmonary edema

- Pulmonary embolism with infarcts

- Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia

- Streptococcus pneumoniae infection

Cite as: Bijin B, Callaway J, Campion J. March 2018 critical care case of the month. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;16(3):117-25. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc035-18 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Ghost in the Machine

Ross Davidson, DO

Michel Boivin, MD

Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

Albuquerque, NM USA

A 53-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after a sudden cardiac arrest at home. The patient had a history of asthma and tracheal stenosis and had progressive shortness of breath over the previous days. The patient’s family noticed a “thump” sound from the patient’s room, and found her apneic. They called 911 and began cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Paramedics arrived on the scene, found an initial rhythm of pulseless electrical activity. The patient eventually achieved return of spontaneous circulation and was transported to the hospital. On arrival the patient was in normal sinus rhythm, with a heart rate of 110 beats per minute. Blood pressure was 80/45 mmHg, on an epinephrine infusion. The patient was afebrile, endotracheally intubated, unresponsive and ventilated at 30 breaths per minute. An initial chest radiograph was compatible with aspiration pneumonitis and a small pneumothorax. Initial electrocardiogram on arrival had 1mm ST-segment depressions in leads V4 to V6. Transthoracic echocardiography was unsuccessful due to patient’s habitus and mechanical ventilation. Because of the patient’s hemodynamic instability and unknown cause of cardiac arrest, an urgent trans-esophageal echocardiogram (TEE) was performed (Videos 1-3).

Video 1. Mid-esophageal 4-chamber view of the heart.

Video 2. Upper esophageal long-axis view of the pulmonary artery and short axis view of the ascending aorta.

Video 3. Upper esophageal short axis view of the pulmonary artery with the ascending aorta in long axis.

Based on the images presented what do you suspect is the etiology of the patient’s cardiac arrest? (Click on the correct answer for an explanation-no penalty for guessing, you can go back and try again)

Cite as: Davidson R, Boivin M. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: ghost in the machine. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;16(2):76-80. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc027-18 PDF

March 2017 Critical Care Case of the Month

Kyle J. Henry, MD

Banner University Medical Center Phoenix

Phoenix, AZ USA

History of Present Illness

A 50-year-old man presented to the emergency room via private vehicle complaining of 5 days of intermittent chest and right upper quadrant pain. Associated with the pain he had nausea, cough, shortness of breath, lower extremity edema, and palpitations.

Past Medical History, Social History, and Family History

He had a history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus but was on no medications and had not seen a provider in years. He was disabled from his job as a construction worker. He had smoked a pack per day for 30 years. He was a heavy daily ethanol consumer. He had an extensive family history of diabetes.

Physical Examination

- Vitals: T 36.4 C, pulse 106/min and regular, blood pressure 96/69 mm Hg, respiratory rate 19 breaths/min, SpO2 98% on room air

- Lungs: clear

- Heart: regular rhythm without murmur.

- Abdomen: mild RUQ tenderness

- Extremities: No edema noted.

Electrocardiogram

His electrocardiogram is show in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Admission electrocardiogram.

Which of the following are true regarding the electrocardiogram? (Click on the correct answer to proceed to the second of seven pages)

- The lack of Q waves in V2 and V3 excludes an anteroseptal myocardial infarction

- The S1Q3T3 patter is diagnostic of a pulmonary embolism

- There are nonspecific ST and T wave changes

- 1 and 3

- All of the above

Cite as: Henry KJ. March 2017 critical care case of the month. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2017;14(3):94-102. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc021-17 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Unchain My Heart

William Mansfield, MD

Michel Boivin, MD

Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine

Department of Medicine,

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

Albuquerque, NM USA

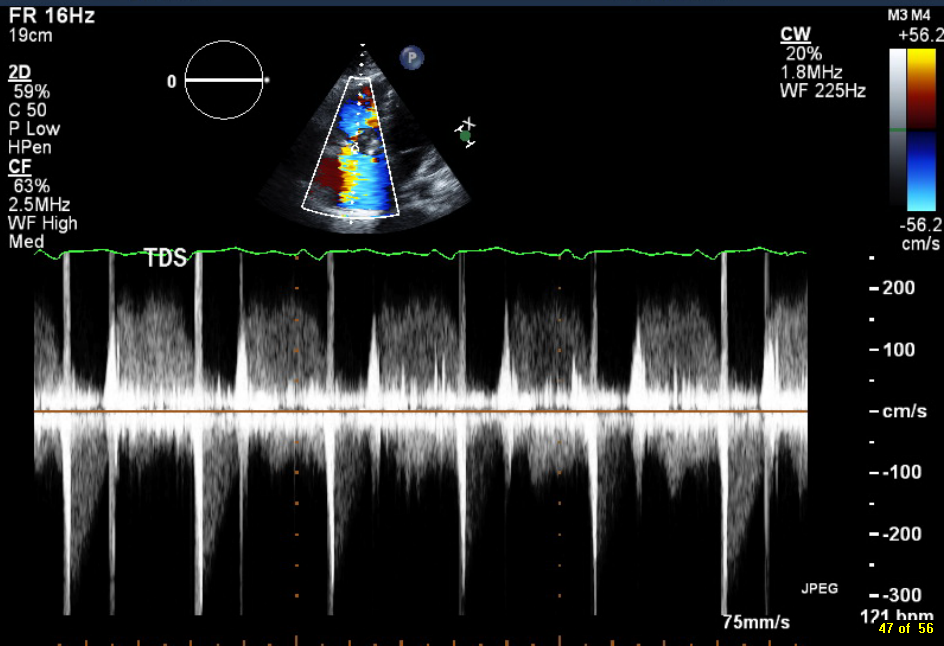

A 46-year-old man presented after a motor vehicle collision. He suffered abdominal injuries (liver laceration, avulsed gall bladder) which were successfully managed non-operatively. The patient remained intubated on mechanical ventilation and remained hypotensive after the injuries resolved. The patient required norepinephrine at low doses to maintain a normal blood pressure. It was noted the patient had a history of remote tricuspid valve replacement. A bedside echocardiogram was then performed to determine the etiology of the patient’s persistent hypotension after hypovolemia had been excluded.

Video 1. Apical four chamber view centered on the right heart.

Video 2. Apical four chamber view centered on the right heart, with color Doppler over the right atrium and ventricle.

Video 3. Right ventricular inflow view.

Figure 1. Continuous-wave Doppler tracing through the tricuspid valve.

What tricuspid pathology do the following videos and images demonstrate? (Click on the correct answer to proceed an explanation and discussion)

Cite as: Mansfield W, Boivin M. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: unchain my heart. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2017;14(2):60-4. doi: http://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc013-17 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: A Pericardial Effusion of Uncertain Significance

Brandon Murguia M.D.

Department of Medicine

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

Albuquerque, NM USA

A 75-year-old woman with known systolic congestive heart failure (ejection fraction of 40%), chronic atrial fibrillation on rivaroxaban oral anticoagulation, morbid obesity, and chronic kidney disease stage 3, was transferred to the Medical Intensive Care Unit for acute hypoxic respiratory failure thought to be secondary to worsening pneumonia.

She had presented to the emergency department 3 days prior with shortness of breath, malaise, left-sided chest pain, and mildly-productive cough over a period of 4 days. She had mild tachycardia on presentation, but was normotensive without tachypnea, hypoxia, or fever. Routine labs were remarkable for a leukocytosis of 15,000 cells/μL. Cardiac biomarkers were normal, and electrocardiogram demonstrated atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular rate of 114 bpm. Chest x-ray revealed cardiomegaly and left lower lobe consolidation consistent with bacterial pneumonia. Patient was admitted to the floor for intravenous antibiotics, cardiac monitoring, and judicious isotonic fluids if needed.

On night 2 of hospitalization, the patient developed respiratory distress with tachypnea, pulse oximetry of 80-85%, and increased ventricular response into the 140 bpm range. The patient remained normotensive. A portable anterior-posterior chest x-ray showed cardiomegaly and now complete opacification of the left lower lobe. She was transferred to the MICU for suspected worsening pneumonia and congestive heart failure.

Upon arrival to the intensive care unit, vital signs were unchanged and high-flow nasal cannula was started at 6 liters per minute. A focused point-of-care cardiac ultrasound (PCU) was done, limited in quality by patient body habitus, but nonetheless demonstrating the clear presence of a moderate pericardial effusion on subcostal long axis view.

Figure 1: Subcostal long axis view of the heart.

What should be done next regarding this pericardial effusion? (Click on the correct answer for the answer and explanation)

- Observe, this is not significant.

- Additional echocardiographic imaging /evaluation.

- Immediate pericardiocentesis.

- Fluid challenge.

Cite as: Murguia B. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: a pericardial effusion of uncertain significance. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2016;13(5):261-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc127-16 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Unraveling a Rapid Drop of Hematocrit

Deepti Baheti, MBBS

Pablo Garcia, MD

Department of Internal Medicine and LifeBridge Critical Care

Sinai Hospital of Baltimore.

Baltimore, MD USA

An 85-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with complaints of shortness of breath on exertion. Her medical history was significant for hypertension, pulmonary embolism and stage III chronic kidney disease. She was diagnosed with severe decompensated pulmonary hypertension and started to improve with diuretics. While hospitalized, she suffered an asystolic arrest and was successfully resuscitated. As a result of chest compressions, the patient developed multiple anterior rib fractures. Within a few days of recovering from her cardiac arrest, she was anticoagulated with enoxaparin as a bridge to warfarin for her prior history of pulmonary embolism. Five days after initiation of enoxaparin and warfarin, she was noted to have an acute drop in her hemoglobin from 8 g/dl to 5 g/dl. A thorough physical examination revealed a large area of swelling in her left anterior chest wall. Point-of- care ultrasound was utilized to image this area of swelling centered at the 3rd intercostal space between the mid-clavicular and anterior axillary line (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Ultrasound image of the chest wall in the sagittal plane.

Figure 2. Ultrasound image of the chest wall in the transverse plane.

What is the cause of this patient’s acute anemia? (Click on the correct answer for an explanation)

Cite as: Baheti D, Garcia P. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: unraveling a rapid drop of hematocrit. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2016;13(2):84-7. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc078-16 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Complication of a Distant Malignancy

S. Cham Sante M.D.1

Michel Boivin M.D.2

Department of Emergency Medicine1

Division of Pulmonary, Critical care and Sleep Medicine2

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

Albuquerque, NM USA

An 82-year-old woman with prior medical history of stage IV colon cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease presented to the medical intensive care unit with newly diagnosed community acquired pneumonia and acute kidney injury. The patient presented with acute onset of shortness of breath, nausea, generalized weakness, bilateral lower extremity swelling and decreased urine output. She was transferred for short term dialysis in the setting of multiple electrolyte abnormalities, including hyperkalemia of 6.4 mmol/l, as well as a creatinine of 6.5 mg/dl. The following imaging of the right internal jugular vein was performed with ultrasound during preparation for placement of a temporary triple lumen hemodialysis catheter.

Figure 1. Panel A: Transverse ultrasound image of the right neck. Panel B: Longitudinal ultrasound image of the right neck, centered on the internal jugular vein.

Based on the above imaging what would be the best location to place the dialysis catheter? (Click on the correct answer for an explanation and discussion)

Cite as: Sante SC, Boivin M. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: complication of a distant malignancy. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2016;13(1):27-9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc055-16 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Now My Heart Is Still Somewhat Full

Krystal Chan, MD

Bilal Jalil, MD

Department of Internal Medicine

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

Albuquerque, NM USA

A 48-year-old man with a history of hypertension, intravenous drug abuse, hepatitis C, and cirrhosis presented with 1 day of melena and hematemesis. While in the Emergency Department, the patient was witnessed to have approximately 700 mL of hematemesis with tachycardia and hypotension. The patient was admitted to the Medical Intensive Care Unit for hypotension secondary to acute blood loss. He was found to have a decreased hemoglobin, elevated international normalized ratio (INR), and sinus tachycardia. A bedside echocardiogram was performed.

Figure 1. Apical four chamber view of the heart.

Figure 2. Longitudinal view of the inferior vena cava entering into the right atrium.

What is the best explanation for the echocardiographic findings shown above? (Click on the correct answer for an explanation and discussion)

Cite as: Chan K, Jalil B. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: now my heart is still somewhat full. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2016;12(6):236-9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc054-16 PDF

June 2016 Critical Care Case of the Month

Theodore Loftsgard APRN, ACNP

Julia Terk PA-C

Lauren Trapp PA-C

Bhargavi Gali MD

Department of Anesthesiology

Mayo Clinic Minnesota

Rochester, MN USA

Critical Care Case of the Month CME Information

Members of the Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and California Thoracic Societies and the Mayo Clinic are able to receive 0.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ for each case they complete. Completion of an evaluation form is required to receive credit and a link is provided on the last panel of the activity.

0.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™

Estimated time to complete this activity: 0.25 hours

Lead Author(s): Theodore Loftsgard, APRN, ACNP. All Faculty, CME Planning Committee Members, and the CME Office Reviewers have disclosed that they do not have any relevant financial relationships with commercial interests that would constitute a conflict of interest concerning this CME activity.

Learning Objectives:

As a result of this activity I will be better able to:

- Correctly interpret and identify clinical practices supported by the highest quality available evidence.

- Will be better able to establsh the optimal evaluation leading to a correct diagnosis for patients with pulmonary, critical care and sleep disorders.

- Will improve the translation of the most current clinical information into the delivery of high quality care for patients.

- Will integrate new treatment options in discussing available treatment alternatives for patients with pulmonary, critical care and sleep related disorders.

Learning Format: Case-based, interactive online course, including mandatory assessment questions (number of questions varies by case). Please also read the Technical Requirements.

CME Sponsor: University of Arizona College of Medicine

Current Approval Period: January 1, 2015-December 31, 2016

Financial Support Received: None

History of Present Illness

A 64-year-old man underwent three vessel coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). His intraoperative and postoperative course was remarkable other than transient atrial fibrillation postoperatively for which he was anticoagulated and incisional chest pain which was treated with ibuprofen. He was discharged on post-operative day 5. However, he presented to an outside emergency department two days later with chest pain which had been present since discharge but had intensified.

PMH, SH, and FH

He had the following past medical problems noted:

- Coronary artery disease

- Coronary artery aneurysm and thrombus of the left circumflex artery

- Dyslipidemia

- Hypertension

- Obstructive sleep apnea, on CPAP

- Prostate cancer, status post radical prostatectomy penile prosthesis

He had been a heavy cigarette smoker but had recently quit. Family history was noncontributory.

Physical Examination

His physical examination was unremarkable at that time other than changes consistent with his recent CABG.

Which of the following are appropriate at this time? (Click on the correct answer to proceed to the second of four panels)

Cite as: Loftsgard T, Terk J, Trapp L, Gali B. June 2016 critical care case of the month. Southwest J Pulm Criti Care. 2016 Jun:12(6):212-5. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc043-16 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Two’s a Crowd

A 43 year old previously healthy woman was transferred to our hospital with refractory hypoxemia secondary to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) due to H1N1 influenza. She had presented to the outside hospital one week prior with cough and fevers. Chest radiography and computerized tomography of the chest revealed bilateral airspace opacities due to dependent consolidation and bilateral ground glass opacities. A transthoracic echocardiogram at the time of the patient’s admission was reported as not revealing any significant abnormalities.

At the outside hospital she was placed on mechanical ventilation with low tidal volume, high Positive end-expiratory pressure (20 cm H20), and a Fraction of inspired Oxygen (FiO2) of 1.0. Paralysis was later employed without significant improvement.

Upon arrival to our hospital, patient was severely hypoxemic with partial pressure of oxygen / FiO2 (P/F) ratio of 43. She was paralyzed with cis-atracurium and placed on airway pressure release ventilation (APRV) with the following settings (pressure high 28 cm H2O, pressure low 0 cm H2O, time high 5.5 sec, time low 0.5 sec). The patient remained severely hypoxemic with on oxygen saturation in the high 70 percent range.

A bedside echocardiogram was performed (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Subcostal long axis echocardiogram.

Figure 2. Subcostal short axis echocardiogram

What abnormality is demonstrated by the short and long axis subcostal views? (Click on the correct answer for an explanation)

Cite as: Abukhalaf J, Boivin M. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: two's a crowd. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2016 Mar;12(3):104-7. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc028-16 PDF

March 2016 Critical Care Case of the Month

Theo Loftsgard APRN, ACNP

Joel Hammill APRN, CNP

Mayo Clinic Minnesota

Rochester, MN USA

Critical Care Case of the Month CME Information

Members of the Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and California Thoracic Societies and the Mayo Clinic are able to receive 0.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ for each case they complete. Completion of an evaluation form is required to receive credit and a link is provided on the last panel of the activity.

0.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™

Estimated time to complete this activity: 0.25 hours

Lead Author(s): Theo Loftsgard APRN, ACNP. All Faculty, CME Planning Committee Members, and the CME Office Reviewers have disclosed that they do not have any relevant financial relationships with commercial interests that would constitute a conflict of interest concerning this CME activity.

Learning Objectives:

As a result of this activity I will be better able to:

- Correctly interpret and identify clinical practices supported by the highest quality available evidence.

- Will be better able to establsh the optimal evaluation leading to a correct diagnosis for patients with pulmonary, critical care and sleep disorders.

- Will improve the translation of the most current clinical information into the delivery of high quality care for patients.

- Will integrate new treatment options in discussing available treatment alternatives for patients with pulmonary, critical care and sleep related disorders.

Learning Format: Case-based, interactive online course, including mandatory assessment questions (number of questions varies by case). Please also read the Technical Requirements.

CME Sponsor: University of Arizona College of Medicine

Current Approval Period: January 1, 2015-December 31, 2016

Financial Support Received: None

History of Present Illness

A 58-year-old man was admitted to the ICU in stable condition after an aortic valve replacement with a mechanical valve.

Past Medical History

He had with past medical history significant for endocarditis, severe aortic regurgitation related to aortic valve perforation, mild to moderate mitral valve regurgitation, atrial fibrillation, depression, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and previous cervical spine surgery. As part of his preop workup, he had a cardiac catheterization performed which showed no significant coronary artery disease. Pulmonary function tests showed an FEV1 of 55% predicted and a FEV1/FVC ratio of 65% consistent with moderate obstruction.

Medications

Amiodarone 400 mg bid, digoxin 250 mcg, furosemide 20 mg IV bid, metoprolol 12.5 mg bid. Heparin nomogram since arrival in the ICU.

Physical Examination

He was extubated shortly after arrival in the ICU. Vitals signs were stable. His weight had increased 3 Kg compared to admission. He was awake and alert. Cardiac rhythm was irregular. Lungs had decreased breath sounds. Abdomen was unremarkable.

Laboratory

His admission laboratory is unremarkable and include a creatinine of 1.0 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) of 18 mg/dL, white blood count (WBC) of 7.3 X 109 cells/L, and electrolytes with normal limits.

Radiography

His portable chest x-ray is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Portable chest x-ray taken on admission to the ICU.

What should be done next? (Click on the correct answer to proceed to the second of five panels)

- Bedside echocardiogram

- Diuresis with a furosemide drip because of his weight gain and cardiomegaly

- Observation

- 1 and 3

- All of the above

Cite as: Loftsgard T, Hammill J. March 2016 critical care case of the month. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2016;12(3):81-8. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc018-16 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Hungry Heart

A 31-year-old incarcerated man with a past medical history of intravenous drug use and hepatitis C, presented with a one week history of dry, non-productive cough, orthopnea and exertional dyspnea. He denied current intravenous drug use, and endorsed that the last time he used was before he was incarcerated over 3 years ago, his last tattoo was in prison, 6 months prior. He was found to have an oxygen saturation of 77% on room air, fever of 40º C, heart rate of 114 bpm, and blood pressure of 80/50 mmHg. The patient had a leukocytosis of 14 x109/L, and a chest x-ray demonstrating patchy airspace disease. Blood cultures were sent and he was treated with antibiotics and vasopressors for septic shock. The patient was intubated for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to multifocal pneumonia. A bedside transthoracic echocardiogram was performed.

Figure 1. Apical four chamber view echocardiogram with color Doppler over the mitral valve.

Figure 2. Right Ventricular (RV) inflow view echocardiogram from same patient What is the likely diagnosis supported by the echocardiogram? (Click on the correct answer for an explanation)

Cite as: Villalobos N, Stoltze K, Azeem M. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: hungry heart. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2016;12(1):24-7. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc007-16 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: The Pleura and the Answers that Lie Within

Heidi L. Erickson MD

Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Occupational Medicine

University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics

Iowa City, IA

A 67-year-old woman with a 40-pack-year smoking history was admitted to the intensive care unit with acute respiratory failure secondary to adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in the setting of pneumococcal bacteremia. On admission, she required endotracheal intubation and vasopressor support. She was ventilated using a low tidal volume strategy and was relatively easy to oxygenate with a PEEP of 5 and 40% FiO2. After 48 hours of clinical improvement, the patient developed sudden onset tachypnea and increased peak and plateau airway pressures. A bedside ultrasound was subsequently performed (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Two- dimensional ultrasound image of the right lung with associated M-mode image.

Figure 2. Two- dimensional ultrasound image of the left lung with associated M-mode image.

What is the cause of this patient’s acute respiratory decompensation and increased airway pressures? (Click on the correct answer for an explanation)

Cite as: Erickson HL. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: the pleura and the answers that lie within. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2015;11(6):260-3. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc149-15 PDF