Critical Care

The Southwest Journal of Pulmonary and Critical Care publishes articles directed to those who treat patients in the ICU, CCU and SICU including chest physicians, surgeons, pediatricians, pharmacists/pharmacologists, anesthesiologists, critical care nurses, and other healthcare professionals. Manuscripts may be either basic or clinical original investigations or review articles. Potential authors of review articles are encouraged to contact the editors before submission, however, unsolicited review articles will be considered.

October 2021 Critical Care Case of the Month: Unexpected Post-Operative Shock

Sooraj Kumar MBBS

Benjamin Jarrett MD

Janet Campion MD

University of Arizona College of Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine and Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Tucson, AZ USA

History of Present Illness

A 55-year-old man with a past medical history significant for endocarditis secondary to intravenous drug use, osteomyelitis of the right lower extremity was admitted for ankle debridement. Pre-operative assessment revealed no acute illness complaints and no significant findings on physical examination except for the ongoing right lower extremity wound. He did well during the approximate one-hour “incision and drainage of the right lower extremity wound”, but became severely hypotensive just after the removal of the tourniquet placed on his right lower extremity. Soon thereafter he experienced pulseless electrical activity (PEA) cardiac arrest and was intubated with return of spontaneous circulation being achieved rapidly after the addition of vasopressors. He remained intubated and on pressors when transferred to the intensive care unit for further management.

PMH, PSH, SH, and FH

- S/P Right lower extremity incision and drainage for suspected osteomyelitis as above

- Distant history of endocarditis related to IVDA

- Not taking any prescription medications

- Current smoker, occasional alcohol use

- Former IVDA

- No pertinent family history including heart disease

Physical Exam

- Vitals: 100/60, 86, 16, afebrile, 100% on ACVC 420, 15, 5, 100% FiO2

- Sedated well appearing male, intubated on fentanyl and norepinephrine

- Pupils reactive, nonicteric, no oral lesions or elevated JVP

- CTA, normal chest rise, not overbreathing the ventilator

- Heart: Regular, normal rate, no murmur or rubs

- Abdomen: Soft, nondistended, bowel sounds present

- No left lower extremity edema, right calf dressed with wound vac draining serosanguious fluid, feet warm with palpable pedal pulses

- No cranial nerve abnormality, normal muscle bulk and tone

Clinically, the patient is presenting with post-operative shock with PEA cardiac arrest and has now been resuscitated with 2 liters emergent infusion and norepinephrine at 70 mcg/minute.

What type of shock is most likely with this clinical presentation?

Cite as: Srinivasan S, Kumar S, Jarrett B, Campion J. October 2021 Critical Care Case of the Month: Unexpected Post-Operative Shock. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2021;23(4):93-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc041-21 PDF

Methylene Blue Treatment of Pediatric Patients in the Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit

Ashley L. Scheffer, MD1,2

Frederick A. Willyerd, MD1,2

Allison L. Mruk, PharmD, BCPPS3

Sarah Patel, BS2

Lucia Mirea, MSc, PhD4

Chasity Wellnitz, RN, BSN, MPH5

Daniel Velez MD2,5

Brigham C. Willis, MD, MEd2,6,7

1Division of Critical Care Medicine, Phoenix Children's Hospital, Phoenix, AZ

2Department of Child Health, University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ

3Department of Pharmacy Services, Phoenix Children's Hospital, Phoenix, AZ

4Department of Biostatistics, Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ

5Division of Cardiovascular Surgery, Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ

6Division of Cardiovascular Intensive Care, Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ

7Department of Pediatrics, University of California Riverside School of Medicine, Riverside, CA

Abstract

Background: In both adults and children, hypotension related to a vasoplegic state has multiple etiologies, including septic shock, burn injury or cardiopulmonary bypass-induced vasoplegic syndrome likely due to an increase in nitric oxide (NO) within the vasculature. Methylene blue is used at times to treat this condition, but its use in pediatric cardiac patients has not been described previously in the literature.

Objective: 1) Analyze the mean arterial blood pressures and vasoactive-inotropic scores of pediatric patients whose hypotension was treated with methylene blue compared to hypotensive controls; 2) Describe the dose administered and the pathologies of hypotension cited for methylene blue use; 3) Compare the morbidity and mortality of pediatric patients treated with methylene blue versus controls.

Design: A retrospective chart review.

Setting: Cardiac ICU in a quaternary care free-standing children’s hospital.

Patients: Thirty-two patients with congenital heart disease who received methylene blue as treatment for hypotension, fifty patients with congenital heart disease identified as controls.

Interventions: None.

Measurements and Main Results: Demographic and vital sign data was collected for all pediatric patients treated with methylene blue during a three-year study period. Mixed effects linear regression models analyzed mean arterial blood pressure trends for twelve hours post methylene blue treatment and vasoactive-inotropic scores for twenty-four hours post treatment. Methylene blue use correlated with an increase in mean arterial blood pressure of 10.8mm Hg over a twelve-hour period (p< 0.001). Mean arterial blood pressure trends of patients older than one year did not differ significantly from controls (p=1.00), but patients less than or equal to one year of age had increasing mean arterial blood pressures that were significantly different from controls (p=0.02). Mixed effects linear regression modeling found a statistically significant decrease in vasoactive-inotropic scores over a twenty-four-hour period in the group treated with methylene blue (p< 0.001). This difference remained significant comparted to controls (p=0.003). Survival estimates did not detect a difference between the two groups (p=0.39).

Conclusion: Methylene blue may be associated with a decreased need for vasoactive-inotropic support and may correlate with an increase in mean arterial blood pressure in patients who are less than or equal to one year of age.

Introduction

One well recognized risk associated with placing patients on cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) during cardiac surgery is vasoplegic syndrome (VS). VS is a constellation of symptoms comprised of hypotension refractory to volume resuscitation and inotropic support, an adequate to high cardiac output state, and low systemic vascular resistance (SVR) (1-4). In adult patients placed on cardiopulmonary bypass the incidence of VS is as high as 4.8%- 8.8% (1,2). For at risk adult populations, such as those who have used heparin, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, or calcium channel blockers pre-operatively, this incidence increases to 44.4%-55.6% (3). Additionally, adult patients who experience vasoplegia after cardiac surgery demonstrate an increased mortality of 10.7%-24% (1,3). Since this syndrome does not respond to conventional fluid resuscitation and vasoactive therapy, patients who experience vasoplegic syndrome often experience poor systemic perfusion that can progress to multisystem organ failure and ultimately death (2).

In both adults and children, hypotension related to a vasoplegic state has multiple etiologies, including septic shock, burn injury or cardiopulmonary bypass-induced vasoplegic syndrome. Various studies have demonstrated an increase in nitric oxide (NO) as the cause of this hypotension (4,6). Vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells contain enzymes that actively produce NO. Vasoplegia is hypothesized to result from the disruption of blood vessel endothelial homeostasis through increased inflammation and dysregulation of the nitric oxide and cyclic guanosine 3’, 5’ monophosphate pathway (cGMP) (5). Published literature demonstrates decreased morbidity and mortality when NO synthesis is inhibited preventing microcirculation impairment (4). Pharmacologic treatments that inhibit NO synthase (NOS) have been developed in an attempt to decrease NO production in disease pathologies where the upregulation of NO causes hypotension. Initial animal and human studies testing nonspecific NOS inhibitors showed NOS inhibition did reduce hypotension and increase systemic vascular resistance (SVR) (8). However, nonspecific NOS inhibition was also associated with severe adverse side effects including myocardial depression with decreased cardiac output, decreased oxygen delivery, and increased mortality, thereby making it unsafe for clinical treatment of vasoplegic syndrome (8).

In order for a pharmacologic agent to successfully inhibit NO, while avoiding serious adverse events, it would theoretically need to inhibit the NO pathway through a different mechanism. In cases of NO upregulation, methylene blue appears to inhibit soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), a downstream biochemical messenger of NO, and ultimately decreases cGMP. cGMP is the final molecular messenger in the NO pathway. Theoretically, decreasing cGMP might avoid the myocardial depression and other adverse side effects seen in nonspecific NO synthase inhibition. Methylene blue is currently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of methemoglobinemia, but has been studied in the medical literature as an off-label treatment for vasoplegic syndrome in adults. Levin et. al. used methylene blue (MB) as a treatment of CPB-induced vasoplegia in adults and showed a reduction in mortality in those who received the treatment (1,6). In a study treating adults with norepinephrine refractory VS Leyh et.al. demonstrated a subsequently higher SVR and decreased need for catecholamine therapy in the methylene blue treatment group (2,6).

Whether methylene blue is an effective treatment for hypotension in pediatric patients in the cardiovascular intensive care unit remains unknown. There is very limited data published on the use of methylene blue in pediatrics. Methylene blue is used, however, in pediatric cardiovascular intensive care units to treat patients experiencing CPB-induced VS refractory to traditional clinical management based on the decreased mortality reported in the adult literature. Pediatric patients represent a subpopulation whose cardiac pathologies vary greatly from the adults examined in published studies. Due to the variability in cardiac pathology, we aim to describe the type of pathologies for which methylene blue was administered. We examine the association between methylene blue and vital sign trends of pediatric patients, specifically mean arterial blood pressures and vasoactive-inotropic scores. Finally, we compare morbidity and mortality of patients who received methylene blue treatment to controls. In this way, our study investigates if methylene blue is a safe and effective treatment, in conjunction with conventional vasopressor therapy, for hypotension in a pediatric population with congenital heart disease.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective chart review study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Phoenix Children’s Hospital and the Institutional Review Board waived the need for subjects to provide informed consent. Electronic medical records were queried to identify patients who were treated with methylene blue in the cardiac intensive care unit of a single, quaternary care free-standing children’s hospital from February 1st, 2013 to June 30th, 2016. A clinically comparable control sample not treated with methylene blue from the same cardiac intensive care unit and time period was identified through a pharmacy database. Control patients received traditional medical therapy for vasoplegia, which included treatment with a combination of epinephrine, vasopressin, and stress dose steroids. Consistent with previous studies, methylene blue was dosed according to weight using a dose of 1-2mg/kg per institutional pharmacy recommendations. This study included any patient who received methylene blue as treatment for hypotension during the study period. Patients who received methylene blue for a diagnostic or radiographic procedure instead of treatment for hypotension were excluded.

For both treated and control patients, trained investigators manually extracted demographic data, vital sign data, and vasoactive-inotropic scores (VIS) during a designated collection period. VIS composite scores reflecting the amount of inotrope and vasopressor support required by infants postoperatively and include dopamine, dobutamine, epinephrine, milrinone, vasopressin, and norepinephrine. As methylene blue has a half-life of five hours, mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) values were collected at the time the medication was administered and at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 hours post treatment, more than two half-lives of the drug. Similarly, VIS were collected at the time of treatment and at 6, 12, 18, and 24 hours post treatment, more than four half-lives of methylene blue. The control cohort had similar electronic medical record data collected for assessment. Morbidity and mortality data for both groups was obtained from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database. Time-to-death in days was computed from the date of surgery to the date of death from all causes.

The distributions of demographic data, baseline clinical factors, cardiac surgical repair, and post-operative conditions were summarized using descriptive statistics for both the methylene blue and control group. Comparison between groups was performed using parametric (Pearson Chi-square test, T-test) or non-parametric (Fisher exact, Wilcoxon rank sum) analyses as appropriate for the data distribution. Similar analysis compared the amount of fluid resuscitation and steroid treatment between patients in the methylene blue group and the control group. Univariate mixed effect models were used to estimate the change in MAP and VIS over time while controlling for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support. Post-operative ventilator support, post-operative complications, length of stay, and mortality were described and compared between the two groups using appropriate statistical tests as listed above. Overall survival was displayed for each group using Kaplan-Meier curves and compared between the two groups using the Log-rank test. All statistical tests were 2-sided with significance evaluated at the 5% level. Analyses were performed using the statistical package SAS (SAS Institute 2011) and STATA (7).

Results

During the study period, methylene blue was administered on thirty-nine occasions to treat thirty-two unique patients. After excluding four patients treated with methylene blue for diagnostic procedures instead of hypotension, the final sample treated with methylene blue included twenty-eight unique patients, of which seven patients were treated twice, resulting in a total of thirty-five methylene blue treatments. Repeat treatments in the same patients were treated as independent events as they were during separate clinical encounters. Indications for using methylene blue included hypotension secondary to cardiogenic shock in seven patients (25%), post cardiopulmonary bypass vasoplegia in sixteen patients (57%), ECMO decannulation hemodynamic instability in two patients (7%), and septic shock in three patients (11%) (Supplemental Digital Content 1). Doses of methylene blue ranged from 0.3mg/kg- 2mg/kg with an average dose of 1.1mg/kg for the treatment cohort.

Among patients less than one year of age, those treated with methylene blue received surgery at a significantly younger age and had a lower mean weight at the time of surgery than did controls (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics for patients treated with methylene blue and controls.

SD = standard deviation

1P-value from Fisher exact test for categorical variables or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous measures.

Congenital heart disease diagnosis was comparable between the two groups, except for tetralogy of Fallot with zero patients (0%) among the methylene blue group, but ten patients (21%) in the control group (Table 1). No significant differences were detected in disease severity as measured by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STAT) Category.

At baseline mean arterial blood pressures (mean ± SD) were significantly lower (T-test p-value = 0.004) in patients treated with methylene blue (45mmHg ± 10) compared to controls (52mmHg ± 10). The average increase in mean arterial blood pressure from baseline to twelve hours did not vary significantly (T-test p-value = 0.40) between methylene blue patients (8.5mmHg ± 13) and controls (5.6mmHg ± 16). However, when analyses were restricted to subjects less than one year of age, a larger increase in mean arterial blood pressure was suggested (T-test p-value = 0.08) for MB patients (8.5 ± 14) compared to controls (1.4 ± 16). Mixed effects linear models examining MAP measurements over time among patients ≤ 1 year with adjustment for ECMO, confirmed a significant increase in MAP over time for those who were treated with MB (slope coefficient = 0.57, p-value <0.001) whereas no trend in MAP values was detected for control patients ≤ 1 year (slope coefficient = 0.08, p-value 0.6). Among patients > 1 year, MAP increased over time for both MB and controls, with no detectable difference between the slopes estimates (Table 2).

Table 2. Mixed effects linear regression analyses examining time trends in mean arterial pressure (MAP) and vasoactive-inotropic score (VIS) of patients treated with methylene blue and controls by age.

MAP= mean arterial pressure; VIS= vasoactive-inotropic scores; SE = standard error

*All models included a random patient-level intercept, assumed unstructured correlation, and were adjusted for ECMO.

Figures 1A and 1B show the MAP measurements over time, and the estimated slopes for MB and control patients adjusted for clustering and ECMO.

Figure 1. Mean arterial blood pressure mixed effects linear regression models stratified by age.

The mean VIS at baseline was significantly higher in MB (27 ± 26) compared to control (12 ± 11) patients (T-test p-value = 0.002). From baseline to 24 hours, MB patients had a significantly larger mean decrease in VIS than controls overall (T-test p-value <0.006). Analyses stratified by age detected a significant negative trend in VIS for MB patients, especially among MB patients > 1 year (Table 2). Weak negative trends in VIS were detected among controls (Figures 2A and 2B).

Figure 2. Vasoactive inotropic score mixed effects linear regression models stratified by age.

Patients treated with methylene blue were extubated approximately twenty-four hours sooner than those in the control group (Table 3).

Table 3. Outcomes among patients treated with methylene blue and controls.

SD = standard deviation

1P-value from Fisher exact test for categorical variables or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous measures

However, methylene blue patients had higher incidence of ECMO support and multisystem organ failure, but a lower incidence of cardiac arrest compared to controls (Table 3). There were no reported adverse effects from methylene blue use. Mortality at thirty days post operatively did not vary significantly between groups (Table 3). At discharge, methylene blue patients had notably higher mortality compared to controls (31% vs. 14%), but statistical significance was not reached (Table 3). There was no difference in length of ICU stay or hospital length of stay between the two groups (Table 3). Furthermore, no significant differences in survival were detected between the methylene blue patients and control patients (Figure 3; Log-rank p-value= 0.39); however, our study was not powered adequately to show equivalence of a clinical outcome.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for patients treated with methylene blue versus controls.

Discussion

Overall, we found that methylene blue use was associated with a decreased need for vasoactive-inotropic support when compared to the control cohort and may correlate with an increase in mean arterial blood pressure over time, specifically in those patients who are less than or equal to one year of age. Vasoplegia results in increased mortality because it often remains resistant to standard clinical interventions such as administration of intravenous fluids and the use of multiple inotropic medications leading to refractory shock and poor oxygen delivery in patients who experience it (2). If a patient’s shock state is unable to be reversed, vasoplegic syndrome (VS) could lead to increased mortality in vulnerable populations such as pediatric patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass for cardiac surgery. In our study, we demonstrated that methylene blue use was associated with an increase in mean arterial blood pressure over a twelve-hour period and a decrease in vasoactive-inotropic scores over a twenty-four-hour period. When compared with controls, the decrease in vasoactive-inotropic score maintained statistical significance in all ages, but mean arterial blood pressure trends were only significant compared to controls in children less than or equal to one year of age. These results support the theory that methylene blue could be an effective treatment for vasoplegia in the pediatric population, although more prospective studies would be needed to verify causation. However, as mentioned above, given the retrospective nature of our study, the difficulty in identifying a more completely matched control cohort (especially for the group of patients <1 year of age), and the limited numbers, such conclusions must be tempered until such trials are performed.

During our evaluation we noted that the increase in mean arterial blood pressure was only statistically significant when ages were stratified. In children older than a year, the increasing mean arterial blood pressure trends observed over time may have resulted from improvement of low cardiac output syndrome after cardiopulmonary bypass since both the control and treatment cohort mixed effects linear regression models had similarly increasing slopes that were not statistically different from each other. In ages less than or equal to one year, however, the control cohort mixed effects linear regression model did not show any trend toward increasing mean arterial blood pressures. Additionally, the methylene blue cohort had an initial lower average mean arterial blood pressure and a statistically significant trend up in mean arterial pressures over a twelve-hour period. Although this subgroup analysis was a smaller sample, the difference in the two regression models suggests that there may be a correlation between the use of methylene blue and increasing mean arterial blood pressures in children less than or equal to one year of age.

Both our treatment cohort and our control cohort were very heterogeneous in certain demographic characteristics, specifically in age and weight, but are very typical of the clinical patient population. Normal values for vital signs such as mean arterial blood pressure vary greatly between ages, which can make statistical interpretation of these vital sign trends difficult. In our study, heterogeneity of age resulted in variability of mean arterial blood pressure data that limited our interpretation of vital signs trends unless age groups were stratified. Ideally, we would have examined all vital sign trends stratified by age to improve the accuracy of our interpretation. However, our population was too small to appropriately power such a subgroup analysis.

Attempting to identify the control group without introducing bias may also have contributed to the difference seen in mean arterial blood pressure trends between the methylene blue cohort and the control cohort. There are multiple factors that control mean arterial blood pressure and vasoactive-inotropic scores. In an attempt to limit cofounding factors, a control group was selected using a pharmacy database that identified patients who received both vasoactive-inotropic treatment and stress dose steroids to treat refractory hypotension after cardiac surgery to find a clinically comparable cohort. The control cohort varied slightly in demographic characteristics, but did not appear statistically different in fluid resuscitation or steroid use (Supplemental Digital Content 2). However, this remains a significant limitation of the current study, given its small numbers, heterogeneous population, and difficulty identifying a better-matched control group. In the future, a prospective, randomized trial of methylene blue in this population could address this.

For adult patients who experienced vasoplegic syndrome, multiple studies have demonstrated an overall reduction in mortality in patients who were treated with methylene blue (1,2,6). However, unlike the adult studies, our study did not find any statistically significant survival difference between the methylene blue cohort and the control cohort. Our study did demonstrate, however, that methylene blue was not associated with increased mortality. Patients treated with methylene blue were also extubated sooner that patients in the control cohort. Speculatively, methylene blue treatment may have been associated with less cardiopulmonary liability, increasing the clinician’s confidence to wean toward extubation sooner than the control group. In addition, our study showed a higher incidence of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support and multisystem organ failure in the methylene blue group as compared to controls. This is likely a result of the high incidence of refractory hypotension and severe shock that led to the use of methylene blue. There was no difference between the two groups in their number of intensive care days or hospital length of stay. No adverse side effects directly attributable to methylene blue were reported in any of our cases, indicating it is a potentially safe treatment for vasoplegic syndrome.

Our study was designed as a retrospective chart review and therefore had limitations inherent with this design. We examined blood pressure trends of any pediatric patient that was given methylene blue for hypotension, regardless of the pathophysiology. Accurately pinpointing the justification for methylene blue treatment retrospectively was difficult especially given the complex nature of the patients’ disease processes, resulting in multiple reasons for hypotension cited in the electronic medical record. We could not accurately limit our patient selection to patients with cardiopulmonary bypass-induced vasoplegia without introducing selection bias and therefore decided to look at all patients who were treated with methylene blue during the study period. Furthermore, limiting our sample size to only those patients who received methylene blue as treatment for post cardiopulmonary bypass vasoplegic syndrome would have resulted in a sample size too small to appropriately power our study.

The definition of vasoplegia requires patients to maintain a high cardiac output state. There were no objective measurements of cardiac output that could be identified retrospectively, thus our study relied on clinician estimation of high cardiac output. In nearly thirty percent of the methylene blue cohort, methylene blue was used as treatment for hypotension that was related to low cardiac output or cardiogenic shock, not vasoplegia. The adult studies that showed a difference in mean arterial blood pressures as well as mortality of patients were examining methylene blue treatment of hypotension secondary to vasoplegic syndrome specifically. Additional prospective studies in pediatric patients are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of methylene blue in treating vasoplegic syndrome.

Conclusion

Methylene blue may be a safe and effective treatment for vasoplegia in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease. Methylene blue use was associated with a decreased need for vasoactive-inotropic support when compared to the control cohort and may correlate with an increase in mean arterial blood pressure over time, specifically in those patients who are less than or equal to one year of age. There was a statistically significant decrease in ventilator days between the methylene blue cohort and the control cohort. There was no difference in survival estimates between those patients who received methylene blue versus controls.

References

- Levin RL, Degrange MA, Bruno GF, Del Mazo CD, Taborda DJ, Griotti JJ, Boullon FJ. Methylene blue reduces mortality and morbidity in vasoplegic patients after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004 Feb;77(2):496-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyh RG, Kofidis T, Strüber M, Fischer S, Knobloch K, Wachsmann B, Hagl C, Simon AR, Haverich A. Methylene blue: the drug of choice for catecholamine-refractory vasoplegia after cardiopulmonary bypass? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003 Jun;125(6):1426-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozal E, Kuralay E, Yildirim V, Kilic S, Bolcal C, Kücükarslan N, Günay C, Demirkilic U, Tatar H. Preoperative methylene blue administration in patients at high risk for vasoplegic syndrome during cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005 May;79(5):1615-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evora PR, Alves Junior L, Ferreira CA, Menardi AC, Bassetto S, Rodrigues AJ, Scorzoni Filho A, Vicente WV. Twenty years of vasoplegic syndrome treatment in heart surgery. Methylene blue revised. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc. 2015 Jan-Mar;30(1):84-92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner I, Guo F, Bogert NV, Stock UA, Meybohm P, Moritz A, Beiras-Fernandez A. Methylene blue modulates transendothelial migration of peripheral blood cells. PLoS One. 2013 Dec 10;8(12):e82214. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar S, Zedan A, Nugent K. Cardiac vasoplegia syndrome: pathophysiology, risk factors and treatment. Am J Med Sci. 2015 Jan;349(1):80-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAS Institute Inc. 2011. Base SAS® 9.3 Procedures Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

- Farina Junior JA, Celotto AC, da Silva MF, Evora PR. Guanylate cyclase inhibition by methylene blue as an option in the treatment of vasoplegia after a severe burn. A medical hypothesis. Med Sci Monit. 2012 May;18(5):HY13-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Víteček J, Lojek A, Valacchi G, Kubala L. Arginine-based inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase: therapeutic potential and challenges. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:318087. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutledge C, Brown B, Benner K, Prabhakaran P, Hayes L. A Novel Use of Methylene Blue in the Pediatric ICU. Pediatrics. 2015 Oct;136(4):e1030-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corral-Velez V, Lopez-Delgado JC, Betancur-Zambrano NL, Lopez-Suñe N, Rojas-Lora M, Torrado H, Ballus J. The inflammatory response in cardiac surgery: an overview of the pathophysiology and clinical implications. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2015;13(6):367-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Scheffer AL, Willyerd FA, Mruk AL, Patel S, Mirea L, Wellnitz C, Velez D, Willis BC. Methylene blue treatment of pediatric patients in the cardiovascular intensive care unit. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2021;23(1):8-17. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc022-21 PDF

Presented, in part, in abstract form at the 2018 Society of Critical Care Medicine Conference in February 25-28, 2018, San Antonio, TX.

The authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Sometimes It’s Better to Be Lucky than Smart

Robert A. Raschke MD and Randy Weisman MD

Critical Care Medicine

HonorHealth Scottsdale Osborn Medical Center

Scottsdale, AZ USA

We recently responded to a code arrest alert in the rehabilitation ward of our hospital. The patient was a 47-year-old man who experienced nausea and diaphoresis during physical therapy. Shortly after the therapists helped him sit down in bed, he became unconsciousness and pulseless. The initial code rhythm was a narrow-complex pulseless electrical activity (PEA). He was intubated, received three rounds of epinephrine during approximately 10 minutes of ACLS/CPR before return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), and was subsequently transferred to the ICU.

Shortly after arriving, a 12-lead EKG was performed (Figure 1), and PEA recurred.

Figure 1. EKG performed just prior to second cardiopulmonary arrest showing S1 Q3 T3 pattern (arrows).

Approximately ten-minutes into this second episode of ACLS, a cardiology consultant informed the code team of an S1,Q3,T3 pattern on the EKG. A point-of-care (POC) echocardiogram performed during rhythm checks was technically-limited, but showed a dilated hypokinetic right ventricle (see video 1).

Video 1. Echocardiogram performed during ACLS rhythm check: Four-chamber view is poor quality, but shows massive RV dilation and systolic dysfunction.

Approximately twenty-minutes into the arrest, 50mg tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) was administered, and return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) achieved two minutes later. A tPA infusion was started. The patient’s chart was reviewed. He had received care in our ICU previously, but this wasn’t immediately recognized because he had subsequently changed his name of record to the pseudonym “John Doe” (not the real pseduonym), creating two separate and distinct EMR records for the single current hospital stay. Review of the first of these two records, identified by his legal name, revealed he had been admitted to our ICU one month previously for a 5.4 x 3.6 x 2.9 cm left basal ganglia hemorrhage. We stopped the tPA infusion.

On further review of his original EMR is was noted that two weeks after admission for intracranial hemorrhage, (and two weeks prior to cardiopulmonary arrest), he had experienced right leg swelling and an ultrasound demonstrated extensive DVT of the right superficial femoral, saphenous, popliteal and peroneal veins. An IVC filter had been due to anticoagulant contraindication. The patient’s subsequent rehabilitation had been progressing well over the subsequent two weeks and discharge was being discussed on the day cardiopulmonary arrest occurred.

On post-arrest neurological examination, the patient gave a left-sided, thumbs-up to verbal request. Ongoing hypotension was treated with a norepinephrine infusion and inhaled epoprostenol. An emergent head CT was performed and compared to a head CT from four weeks previously (Figure 2), showing normal evolution of the previous intracranial hemorrhage without any new bleeding.

Figure 2. CT brain four weeks prior to (Panel A), and immediately after cardiopulmonary arrest and administration of tPA (Panel B), showing substantial resolution of the previous intracranial hemorrhage.

A therapeutic-dose heparin infusion was started. An official echo confirmed the findings of our POC echo performed during the code, with the additional finding of McConnell’s sign. McConnell’s sign is a distinct echocardiographic finding described in patients with acute pulmonary embolism with regional pattern of right ventricular dysfunction, with akinesia of the mid free wall but normal motion at the apex (1). A CT angiogram showed bilateral pulmonary emboli, and interventional radiology performed bilateral thrombectomies. Hypotension resolved immediately thereafter. The patient was transferred out of the ICU a few days later and resumed his rehabilitation.

A few points of interest:

- IVC filters do not absolutely prevent life-threatening pulmonary embolism (2,3).

- Sometimes, serendipity smiles, as when the cardiologist happened into the room during the code, and provided an essential bit of information.

- Emergent POC ultrasonography is an essential tool in the management of PEA arrest of uncertain etiology.

- Barriers to access of prior medical records can lead to poorly-informed decisions. But in this case, ignorance likely helped us make the right decision.

- Giving lytic therapy one month after an intracranial hemorrhage is not absolutely contra-indicated when in dire need.

- As the late great intensivist, Jay Blum MD used to say: “Sometimes it’s better to be lucky than smart.”

References

- Ogbonnah U, Tawil I, Wray TC, Boivin M. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: Caught in the act. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;17(1):36-8. [CrossRef]

-

Urban MK, Jules-Elysee K, MacKenzie CR. Pulmonary embolism after IVC filter. HSS J. 2008 Feb;4(1):74-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

PREPIC Study Group. Eight-year follow-up of patients with permanent vena cava filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism: the PREPIC (Prevention du Risque d'Embolie Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave) randomized study. Circulation. 2005 Jul 19;112(3):416-22. doi: [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Raschke RA, Weisman R. Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Sometimes It’s Better to Be Lucky than Smart. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2021;22(6):116-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc016-21 PDF

Amniotic Fluid Embolism: A Case Study and Literature Review

Ryan J Elsey DO1*, Mary K Moats-Biechler OMS-IV2, Michael W Faust MD3, Jennifer A Cooley CRNA-APRN4, Sheela Ahari MD4, and Douglas T Summerfield MD1

Departments of Internal Medicine1,Obstetrics and Gynecology3,and Anesthesia4

1Mercy Medical Center—North Iowa

Mason City, IA USA

2A.T. Still University

Kirksville, MO USA

Abstract

Amniotic fluid embolus is a rare and life threatening peripartum complication that requires quick recognition and emergent interdisciplinary management to provide the best chance of a positive outcome for the mother and infant. The following case study demonstrates the importance of quick recognition as well as an interdisciplinary approach in caring for such a condition. A literature review regarding the current recommendations for management of this condition follows as well as a proposed treatment algorithm.

Introduction

Amniotic fluid embolus (AFE) is a rare and life-threatening complication of pregnancy; a recent population-based review found an estimated incidence ranging from 1 in 15,200 deliveries in North America and 1 in 53,800 deliveries in Europe (1). Mortality rates vary but have been reported to range from 11% to more than 60%, with the most recent population-based studies in the United States reporting a 21.6% fatality rate (1-4). Despite best efforts, it remains one of the leading causes of maternal death (1,5,6). However, rapid diagnosis of AFE and immediate obstetric and intensive care has proven to play a decisive role in maternal prognosis and survival (7-9).

In 2016, uniform diagnostic criteria were proposed for reporting on cases of AFE. First, a report of AFE requires a sudden onset of cardiorespiratory arrest, which consists of both hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg) and respiratory compromise (dyspnea, cyanosis, or SpO2 < 90%). Secondly, overt disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) must be documented following the appearance of signs or symptoms using a standardized scoring system. Coagulopathy must be detected prior to a loss of sufficient blood to account for dilutional or shock-related consumptive coagulopathy. Third, the clinical onset must occur during labor or within 30 minutes of delivery of the placenta. Fourth, no fever ≥ 38.0° C during labor can occur (10).

The following case study qualifies as a reportable incidence of an AFE under the above criteria and further demonstrates the ability to successfully stabilize a patient with AFE due to quick recognition, interdisciplinary cooperation, and effective supportive management.

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old gravida 5, para 1-1-2-2, presented at 36 weeks and 1-day gestation for induction of labor. Her past medical history included esophageal atresia at birth and a past pregnancy complicated by preterm, premature rupture of the membranes. Initial labs at admission were significant for a hemoglobin of 12.2 g/dL and a platelet count of 234 x103 u/L. The patient was subsequently started on lactated ringers at 125 ml/hr. As the patient's labor progressed, an epidural was placed 3 hours after admission. Four hours and 42 minutes after admission, an artificial rupture of the membranes was performed.

Eighteen minutes after the artificial rupture of the membranes was performed, the patient was noted to have seizure-like activity. She was given an intravenous (IV) fluid bolus and ephedrine, and the anesthesia provider was emergently contacted. When anesthesia arrived, the patient was noted to be cyanotic in bed. Patient vitals and exam were significant for emesis, a heart rate of 50 beats per minute (bpm), systolic blood pressure in the low 70s (mmHg), and a fetal heart rate in the 70s.

The differential diagnosis at this time was broad and included anesthesia drug reactions such as an intravascular epidural migration, pulmonary thromboembolism, eclampsia, or even an aortic dissection. A pulmonary embolism was felt to be unlikely due to the patient's bradycardia and sudden neurologic changes. Eclampsia was less likely at the time due to no signs of pre-eclampsia in the patient as well as the patient's current bradycardia and hypotension. Given the patient's absence of Marfan syndrome, aortic dissection was not considered to be a high probability. The patient did have signs consistent with an intravascular epidural including altered mental status, cyanosis, bradycardia, hypotension, vomiting, and a low fetal heart rate. However, at the time anesthesia felt she was more likely suffering from an acute embolic process given the timeframe between the artificial rupture of the membranes and the onset of her symptoms.

Given the patient's instability, she was emergently taken for a cesarean section and intubated to provide airway stabilization. The cesarean section began 15 minutes after seizure like symptoms started and upon delivery, the infant was subsequently transferred to a tertiary center for therapeutic hypothermia.

Intraoperatively, the patient was noted to maintain a peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2) of >90%. However, end tidal C02 was elevated to 54 mmHg despite hyperventilation and peak airway pressures were elevated to 38 cmH2O. Albuterol and sevoflurane were subsequently utilized in an attempt to increase bronchodilation. Following completion of the caesarian section, peak airway pressures normalized to less than 30 cmH2O but end tidal CO2 levels remained as high as 52 mmHg despite hyperventilation. Blood pressure was significant for systolic pressure of 80 mmHg. IV phenylephrine was administered. Additionally, uterine massage was performed to aid in hemorrhage control and the patient was administered IV oxytocin, methylergonovine maleate, carboprost, and vaginal misoprostol. A repeat complete blood count was performed one hour after symptom onset which showed a hemoglobin of 10.3 g/dL and a platelet count of 103 x103 u/L.

In this case, the patient’s care team had a high suspicion of an AFE with symptoms that followed the uniform diagnostic criteria for an AFE. The patient had hemodynamic instability, coinciding with the recent rupture of membranes. Her systolic blood pressure was < 90 mmHg and her end tidal C02 levels (in mmHg) were elevated to the high 40s and low 50s. The critical care team was notified of her condition and the patient was subsequently transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) on mechanical ventilation and sedated with fentanyl and versed.

Upon arrival to the ICU, a DIC panel was performed revealing DIC. Labs showed a fibrinogen level of 52 mg/dL, A D-dimer greater than 128,000 ng/mL, and a platelet count of 80,000 u/L despite the administration of one pooled unit of platelets. The patient's international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.3 with a baseline INR of 0.9. Due to multiple laboratory abnormalities and a clinical condition consistent with DIC, aggressive transfusions were performed per the standard of care for patients suffering with DIC. A peripheral smear was obtained revealing schistocytes (Figure 1) which verified the DIC diagnosis.

Figure 1. The patient's peripheral blood smear four hours after onset of symptoms which demonstrates schistocytes indicative of DIC.

Hematology was emergently consulted and it was recommended to avoid additional platelet transfusions unless platelet counts dropped below 10,000 to 20,000 u/L. One milligram (mg) of subcutaneous phytonadione was also given five hours after symptom onset in an effort to decrease bleeding.

Cardiology was consulted and performed an emergent echocardiogram to assess the patient’s heart function and rule out any cardiac abnormalities. Given her past history of esophageal atresia, there was particular concern about an underlying ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, or tetralogy of Fallot (11). The echocardiogram revealed a dilated, yet functional right ventricle, which was expected in the setting of an AFE. ICU physicians at a tertiary care center were provisionally consulted to confirm that the patient was a candidate for arteriovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (AV-ECMO) should she suffer further cardiopulmonary collapse. Labs, including hemoglobin, platelets, fibrinogen activity, and ionized calcium were drawn every two hours during the acute phase of the patient's management and abnormalities were addressed as required over the subsequent two hours. The patient's hemoglobin was noted to decline to as low as 6.7 g/dL. Of note, lab draws did suffer some sample lysis due to the patient's coagulation abnormalities. The patient did initially require phenylephrine for blood pressure support. Additionally, she was placed on an experimental septic shock protocol which involved the administration of 1500 mg of ascorbic acid every six hours, 60 mg of methylprednisolone every six hours, and 200 mg of thiamine every 12 hours. The patient began to stabilize around 10 to 12 hours after her AFE symptoms began and pressor support was titrated off, at which point blood draws were liberalized to every four hours. The patient continued to improve and remained stable overnight.

On hospital day two, the patient was noted to be alert and was successfully extubated. Following extubation, the physical exam found her to be neurologically and hemodynamically intact. During her stay in the ICU, the patient received a total of eight units of packed red blood cells, five units of fresh frozen plasma, one pooled unit of platelets, and one unit of cryoprecipitate. The patient was ultimately discharged from the hospital on day four with no long-term sequelae noted.

The patient was informed that data from the case would be submitted for publication and gave her consent.

A Review of the Literature

AFE remains one of the leading causes of direct, maternal mortality among developed countries (1,12,13). Multiple reviews have studied the incidence of AFE, which varies widely, from 1.9 per 100,000 to 7.7 per 100,000 pregnancies, with the reported fatality rate due to AFE ranging from 11% to more than 60%, depending on the study (1,2,4,14). The difficulty in reporting an accurate incidence and fatality rate is likely secondary to the fact that AFE remains a diagnosis of exclusion. AFE is traditionally diagnosed clinically during labor in a woman with ruptured membranes and a triad of symptoms, including unexplained cardiovascular collapse, respiratory distress, and DIC. (1,2,15-18). Additional symptoms may include hypotension, frothing from the mouth, fetal heart rate abnormalities, loss of consciousness, bleeding, uterine atony, and seizure-like activity (15,16,19).

The majority of women who fail to survive an AFE die during the acute phase (median of one hour and 42 minutes after presentation) (2,6). Surviving beyond the acute phase dramatically improves their overall chance of survival; however, survival is not without long term morbidities. Analysis performed in the United Kingdom in 2005 and again in 2015 showed that 7% of woman surviving AFE have permanent neurological injury, including persistent vegetative state/anoxic/hypoxic brain injury or cerebrovascular accident (2,7). Among survivors,17% were shown to have other comorbidities, including sepsis, renal failure, thrombosis or pulmonary edema and 21% required a hysterectomy (2,6).

Despite several decades of research, the pathogenesis of an AFE continues to remain somewhat clouded. Multiple theories have been postulated concerning the clinical manifestations occurring with an AFE and their relationship with the passage of amniotic fluid into the systemic maternal circulation. The first theory proposed described amniotic debris passing through the veins of the endocervix and into maternal circulation, resulting in an obstruction (1,6). This theory has fallen out of favor as there is no physical evidence of obstruction noted on radiologic studies, autopsies, or experimentally in animal models (1,20,21). Additionally, multiple studies have found that that the passage of amniotic and fetal cells into maternal circulation are very common during pregnancy and delivery (6). Thus, most theories today focus on humoral and immunological factors and how they affect the body (5,22,23). Current research focuses on the effect of amniotic fluid on the body after it has already entered into maternal circulation. It is theorized that the amniotic fluid results in the release of various endogenous mediators, resulting in the physiologic changes that are seen with an AFE. Proposed mediators include histamine (22), bradykinin (24), endothelin (25,26), leukotrienes (27), and arachidonic acid metabolites (28).

The hemodynamic response to AFE is biphasic in nature. It consists of vasospasm, resulting in severe pulmonary hypertension, and intense vasoconstriction of the pulmonary vasculature secondary to the amniotic fluid itself, which can lead to ventilation-perfusion mismatch and resultant hypoxia (5,6,29). On an echocardiogram, the initial phase of an AFE consists of right ventricular failure demonstrated by a severely dilated, hypokinetic right ventricle with deviation of the interventricular septum into the left ventricle (18). Following the initial phase of right ventricular failure, which can lasts minutes to hours, left ventricular failure along with cardiogenic, pulmonary edema becomes the prominent finding (1,5). This occurs due to a reduction in preload as well as systemic hypotension. These changes may decrease coronary artery perfusion, which can result in myocardial injury, precipitation of cardiogenic shock, and worsening of distributive shock (1,6,30).

DIC is present in up to 83% of patients experiencing an AFE; however, its onset during presentation can be variable (31). It may present within the first ten minutes following cardiovascular collapse, or it may precipitate up to nine hours following the initial clinical manifestation (5,31,32). The precipitating pathophysiology behind DIC in AFE is poorly understood, but is likely to be consumptive, rather than fibrinolytic, in nature. In an AFE it is currently theorized that tissue factor, which is present in amniotic fluid, activates the extrinsic pathway by binding with factor VII, triggering clotting to occur by activating factor X, resulting in the consumptive coagulopathy (1,33-35). Ultimately, it is felt that this coagulation leads to vasoconstriction of the microvasculature and thrombosis by producing thrombin that is secreted into the endothelin, leading to the changes seen in DIC (1,5,6,14,18).

Recommended Management for AFE Based on Current Literature

Early recognition of AFE and immediate obstetric and intensive care has proven to play a decisive role in maternal prognosis and survival (7,8). In order to survive an an AFE, patients require immediate multidisciplinary management with a focus on maintaining oxygenation, circulatory support, and correcting coagulopathy (1,6).

A literature review of the current management for patients presenting with AFE recommends standard initial lifesaving supportive care. This should begin with immediate protection of the patient's airway via endotracheal intubation and early, sufficient oxygenation using an optimized positive end-expiratory pressure (FiO2:PEEP) ratio, which also decreases the risk of aspiration (1,5,29). Two large bore IV lines should be placed for crystalloid fluid resuscitation. In the setting of a cardiopulmonary arrest, cardiopulmonary resuscitation should be initiated and an immediate caesarian section within three to five minutes should be performed in the presence of a fetus ≥ 23 weeks gestation (5,18,36-38). This serves several purposes, including decreasing the risk of the infant suffering from long term neurologic injury secondary to hypoxia, improving venous flow to the right heart by emptying the uterus, and reducing pressure on the inferior vena cava to decrease impedance to blood flow, which decreases systemic blood pressure (1,5,31,39,40).

During the initial phase, attention should be paid to avoid hypoxia, acidosis, and hypercapnia due to their ability to increase pulmonary vascular resistance and lead to worsening of right heart failure and recommendations include sildenafil, inhaled or injected prostacyclin, and inhaled nitric oxide (6). Recommendations to treat for hypotension during this phase include the utilization of vasopressors, such as norepinephrine or vasopressin (1,6,18,37,41). Hemodynamic management during the second phase should focus on the patient's left-sided heart failure by optimizing cardiac preload via vasopressors to maintain perfusion and utilizing inotropes such as dobutamine or milrinone to increase left ventricular contractility (1,6,18).

Due to the relationship between AFE and DIC, current recommendations suggest early assessment of the patient's coagulation status. Additionally, in the setting of a massive hemorrhage, blood product administration should not be delayed while awaiting laboratory results (18). Early corrective management of the patient's coagulopathy should be aggressive in nature, especially in the setting of a massive hemorrhage. Tranexamic acid and fibrinogen concentrate (for fibrinogen levels below 2 g/L) are essential in the treatment of hyper-fibrinolysis. Additionally, multiple obstetric case studies have shown fibrinogen replacement to benefit from bedside rotational thromboelastometry if available due to its ability to rapidly diagnosis consumptive versus fibrinolytic coagulopathy at the bedside (5,42,43). Hemostatic resuscitation with packed red blood cells, fresh-frozen plasma, and platelets at a ratio of 1:1:1 should be administered (6,18). Cryoprecipitate replacement is recommended as well due to the consumptive nature of DIC in AFE, and its importance should not be understated. A 2015 population-based cohort study showed that women with AFE who died or had permanent neurologic injury were less likely to have received cryoprecipitate than those who survived and were without permanent neurologic injury (1,2). Furthermore, due to the dynamic processes of chemodynamical labs, including hemoglobin, platelet count, and fibrinogen must be monitored closely to prevent complications or over transfusion (14).

Uterine atony is a common feature with AFE and it is recommended to immediately administer uterotonics during the postpartum period to prevent its occurrence (5,44). Should it occur, uterine atony should be managed aggressively via uterotonics such as oxytocin, ergot derivatives, and prostaglandins; refractory cases may require packing material for uterine tamponade, uterine artery ligation, or even a hysterectomy for the most severe (5,8,18).

In addition to the treatments listed above, multiple case reports support the use of aggressive or novel therapeutic modalities to aid in the treatment of AFE; however, for many of the treatments, evidence supporting increased survival of an AFE is merely anecdotal (18). Among the best supported ancillary treatments is nonarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a possible therapeutic treatment for patients with refractory acute respiratory distress syndrome. However, due to the profoundly coagulopathic state of AFE and the active hemorrhage occurring with AFE, the use of anticoagulation may profoundly worsen bleeding. Consequently, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation is controversial and not routinely recommended in the management of AFE (6,18). Similarly, post-cardiac arrest therapeutic hypothermia with a range of 32°C to 34°C is often avoided in patients with AFE due to the increased risk of hemorrhage given their predisposition for DIC (18). However, in patients not demonstrating DIC and overt bleeding, targeted temperature management to 36°C and preventing hyperthermia is an option that should be considered (17,45,46). Factor VIIa procoagulant, which increases thrombin formation, has been utilized anecdotally, but strong supporting data is lacking; it should only be considered if following the replacement with massive coagulation factors, hemostasis and bleeding fail to improve (5,47). Additionally, it is important to note that factor VIIa replacement is only effective if other clotting factors have been replaced (1,6,48,49). Novel therapeutic modalities mentioned in the literature also include continuous hemofiltration, cardiopulmonary bypass, nitric oxide, steroids, C1 esterase inhibitor concentrate, and plasma exchange transfusion. While there are case reports published to suggest that all of the aforementioned therapies may provide some level of improvement in patients with AFE, the positive results from these cases may be due to their administration during the intermediate phase of AFE as opposed to the acute phase of AFE, where the majority of mortality occurs—once patients have surpassed the early, acute phase, survival chances greatly improve with continued supportive care (1,6).

AFE has traditionally been viewed as a condition associated with poor outcomes and a high mortality rate for both the mother and the infant. However, with quick AFE recognition, high quality supportive care, and interdisciplinary cooperation, patients can have positive outcomes. Based on the success with the patient presented in this case and the review of the current literature as seen above, the authors have proposed an algorithm (Figure 2) for the treatment of future patients experiencing AFE.

Figure 2. Proposed interdisciplinary treatment algorithm for acute management of an AFE.

By following the algorithm, the authors believe that the outcomes for AFE patients can be improved.

Abbreviations

PEEP: positive end-expiratory pressure; BP: blood pressure; TV: tidal volume; ACLS: Advanced cardiac life support; ABG: Arterial blood gas; CBC: Complete blood count; CMP: Complete metabolic profile; INR: International normalized ratio; PTT: Partial prothrombin time; ART line: Arterial line; NO: Nitric oxide; ARDS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome; ECMO: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FFP: Fresh frozen plasma; Plt: Platelet; pRBCs: Packed red blood cells; NE: Norepinephrine.

References

- Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R. Amniotic fluid embolism: an evidence-based review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(5):445-e1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick D, Tuffnell D, Kurinczuk J, Knight M. Incidence, risk factors, management and outcomes of amniotic-fluid embolism: a population-based cohort and nested case-control study. BJOG. 2016 Jan;123(1):100-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham FG, Nelson BD. Disseminated intravascular coagulation syndromes in obstetrics. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(5):999-1011. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight M, Berg C, Brocklehurst P, et al. Amniotic fluid embolism incidence, risk factors and outcomes: a review and recommendations. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012 Feb 10;12:7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath WH, Hofer S, Sinicina I. Amniotic fluid embolism: an interdisciplinary challenge: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2014;111(8):126. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuffnell DJ, Slemeck E. Amniotic fluid embolism. Obstetrics,Gynaecology & Reproductive Medicine. 2017;27(3):86-90. [CrossRef]

- Tuffnell D. United Kingdom amniotic fluid embolism register. BJOG. 2005;112(12):1625-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda Y, Kamitomo M. Amniotic fluid embolism: a comparison between patients who survived and those who died. J Int Med Res. 2009;37(5):1515-1521. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CEMACH. Confidential enquiry into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom,why mothers die 2000-2002. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 2004.

- Clark SL, Romero R, Dildy GA, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for the case definition of amniotic fluid embolism in research studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4):408-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark DC. Esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59(4):910-916,919-20. [PubMed]

- Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Syverson C, Henderson Z. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States,1998 to 2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1302-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, et al. Saving Mothers' Lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006-2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG. 2011;118 Suppl 1:1-203. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erez O, Mastrolia SA, Thachil J. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in pregnancy: insights in pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):452-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezai S, Hughes AC, Larsen TB, Fuller PN, Henderson CE. Atypical amniotic fluid embolism managed with a novel therapeutic regimen. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2017;2017:8458375. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark SL. Amniotic fluid embolism. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 Pt 1):337-48. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark SL, Montz FJ, Phelan JP. Hemodynamic alterations associated with amniotic fluid embolism: a reappraisal. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151(5):617-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco LD, Saade G, Hankins GD, Clark SL. Amniotic fluid embolism: diagnosis and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(2):B16-24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark SL. Amniotic fluid embolism. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53(2):322-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolte L, van Kessel H, Seelen J, Eskes T, Wagatsuma T. Failure to produce thesyndrome of amniotic fluid embolism by infusion of amniotic fluid and meconium into monkeys. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1967;98(5):694-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamsons K, Mueller-Heubach E, Myers RE. The innocuousness of amniotic fluid infusion in the pregnant rhesus monkey. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;109(7):977-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson MD. A hypothesis regarding complement activation and amniotic fluid embolism. Med Hypotheses. 2007;68(5):1019-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson MD. Current concepts of immunology and diagnosis in amniotic fluid embolism. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:946576. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robillard J, Gauvin F, Molinaro G, Leduc L, Adam Arrived GE. The syndrome of amniotic fluid embolism: a potential contribution of bradykinin. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(4):1508-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- el Maradny Kandalama Halim A, Maehara K, Terao T. Endothelin has a role in early pathogenesis of amniotic fluid embolism. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1995;40(1):14-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khong TY. Expression of endothelin‐1 in amniotic fluid embolism and possible pathophysiological mechanism. BJOG. 1998;105(7):802-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azegami Memoria N. Amniotic fluid embolism and leukotrienes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155(5):1119-24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark SL. Arachidonic acid metabolites and the pathophysiology of amniotic fluid embolism. Semin Reprod Endocrinol. 1985;3:253-7. [CrossRef]

- Stafford I, Sheffield J. Amniotic fluid embolism. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2007;34(3):545-53,xii. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner PE, Lushbaugh CC, Frank HA. Fatal obstetric shock for pulmonary emboli of amniotic fluid. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1949;58(4):802-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark SL, Hankins GD, Dudley DA, Dildy GA, Porter TF. Amniotic fluid embolism: analysis of the national registry. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(4 Pt 1):1158-67; discussion 1167-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean LS, Rogers RP,3rd, Harley RA, Hood DD. Case scenario: amniotic fluid embolism. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(1):186-92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood CJ, Bach R, Guha A, Zhou XD, Miller WA, Nemerson Y. Amniotic fluid contains tissue factor, a potent initiator of coagulation. Am J Obstet Gynecol.1991;165(5 Pt 1):1335-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall RJ, Duke GJ. Amniotic fluid embolism syndrome: case report and review. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1995;23(6):735-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uszynski M, Zekanowska E, Uszynski W, Kuczynski J. Tissue factor (TF) and tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) in amniotic fluid and blood plasma: implications for the mechanism of amniotic fluid embolism. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;95(2):163-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeejeebhoy FM, Zelop CM, Lipman S, et al. Cardiac Arrest in Pregnancy: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(18):1747-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Shea A, Eappen S. Amniotic fluid embolism. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2007;45(1):17-28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies S. Amniotic fluid embolus: a review of the literature. Can J Anaesth. 2001;48(1):88-98. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin RW. Amniotic fluid embolism. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1996;39(1):101-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin PS, Leaton MB. Emergency. Amniotic fluid embolism. Am J Nurs. 2001;101(3):43-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore J, Baldisseri MR. Amniotic fluid embolism. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(10 Suppl):S279-285.[CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins NF, Bloor M, McDonnell NJ. Hyperfibrinolysis diagnosed by rotational thromboelastometry in a case of suspected amniotic fluid embolism. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2013;22(1):71-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loughran JA, Kitchen TL, Sindhaker S, Ashraf M, Awad M, Kealaher EJ. Rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM®)-guided diagnosis and management of amniotic fluid embolism. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2018. Sep 11. pii: S0959-289X(18)30122-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuffnell D, Knight M, Plaat F. Amniotic fluid embolism - an update. Anaesthesia. 2011;66(1):3-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen N, Wetterslev J, Cronberg T, et al. Targeted temperature management at 33 C versus 36 C after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2197-206. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaway CW, Donnino MW, Fink EL, et al. Part 8: Post-cardiac arrest care: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2015;132(18 Suppl 2):S465-82. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leighton BL, Wall MH, Lockhart EM, Phillips LE, Zatta AJ. Use of recombinant factor VIIa in patients with amniotic fluid embolism: a systematic review of case reports. Anesthesiology. 2011;115(6):1201-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosper SC, Goudge CS, Lupo VR. Recombinant factor VIIa after amniotic fluid embolism and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 pt 2):524-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim Y, Loo CC, Chia V, Fun W. Recombinant factor VIIa after amniotic fluid embolism and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;87(2):178-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Elsey RJ, Moats-Biechler MK, Faust MW, Cooley JA, Ahari S, Summerfield DT. Amniotic fluid embolism: A case study and literature review. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2019;18(4):94-105. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc105-18 PDF

May 2018 Critical Care Case of the Month

Lacey Gagnon APRN, CNP

Theo Loftsgard APRN, CNP

Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care

Mayo Clinic Minnesota

Rochester, MN USA

Chief Complaint

Shortness of breath

History of Present Illness

The patient is a 44-year-old woman who was admitted with a history of “pericarditis”. She has a several years history of progressive shortness of breath, abdominal distention and lower extremity edema.

Past Medical History, Social History and Family History

She has a history of obesity, poorly controlled type 2 diabetes, uterine fibroids and hypertension. She does not smoke but does have 1-2 alcoholic beverages per day. Family history is noncontributory.

Physical Examination

- Vital signs: pulse 96 beats/min, blood pressure 110/85 mm Hg, temperature 37° C, respirations 18 breaths/min.

- Neck: there is jugular venous distention with a positive hepatojugular reflux.

- Lungs: rales at both bases.

- Heart: regular rhythm without murmur.

- Abdomen: Distended. Shifting dullness is present.

- Extremities: 2-3 pretibial pitting edema.

Chest Radiography

Chest x-ray shows a small right pleural effusion with mild vascular congestion at the bases. Heart size is normal.

Which of the following should be performed?

Cite as: Gagnon L, Loftsgard T. May 2018 critical care case of the month. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;16(5):245-51. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc048-18 PDF

March 2017 Critical Care Case of the Month

Kyle J. Henry, MD

Banner University Medical Center Phoenix

Phoenix, AZ USA

History of Present Illness

A 50-year-old man presented to the emergency room via private vehicle complaining of 5 days of intermittent chest and right upper quadrant pain. Associated with the pain he had nausea, cough, shortness of breath, lower extremity edema, and palpitations.

Past Medical History, Social History, and Family History

He had a history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus but was on no medications and had not seen a provider in years. He was disabled from his job as a construction worker. He had smoked a pack per day for 30 years. He was a heavy daily ethanol consumer. He had an extensive family history of diabetes.

Physical Examination

- Vitals: T 36.4 C, pulse 106/min and regular, blood pressure 96/69 mm Hg, respiratory rate 19 breaths/min, SpO2 98% on room air

- Lungs: clear

- Heart: regular rhythm without murmur.

- Abdomen: mild RUQ tenderness

- Extremities: No edema noted.

Electrocardiogram

His electrocardiogram is show in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Admission electrocardiogram.

Which of the following are true regarding the electrocardiogram? (Click on the correct answer to proceed to the second of seven pages)

- The lack of Q waves in V2 and V3 excludes an anteroseptal myocardial infarction

- The S1Q3T3 patter is diagnostic of a pulmonary embolism

- There are nonspecific ST and T wave changes

- 1 and 3

- All of the above

Cite as: Henry KJ. March 2017 critical care case of the month. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2017;14(3):94-102. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc021-17 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Unchain My Heart

William Mansfield, MD

Michel Boivin, MD

Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine

Department of Medicine,

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

Albuquerque, NM USA

A 46-year-old man presented after a motor vehicle collision. He suffered abdominal injuries (liver laceration, avulsed gall bladder) which were successfully managed non-operatively. The patient remained intubated on mechanical ventilation and remained hypotensive after the injuries resolved. The patient required norepinephrine at low doses to maintain a normal blood pressure. It was noted the patient had a history of remote tricuspid valve replacement. A bedside echocardiogram was then performed to determine the etiology of the patient’s persistent hypotension after hypovolemia had been excluded.

Video 1. Apical four chamber view centered on the right heart.

Video 2. Apical four chamber view centered on the right heart, with color Doppler over the right atrium and ventricle.

Video 3. Right ventricular inflow view.

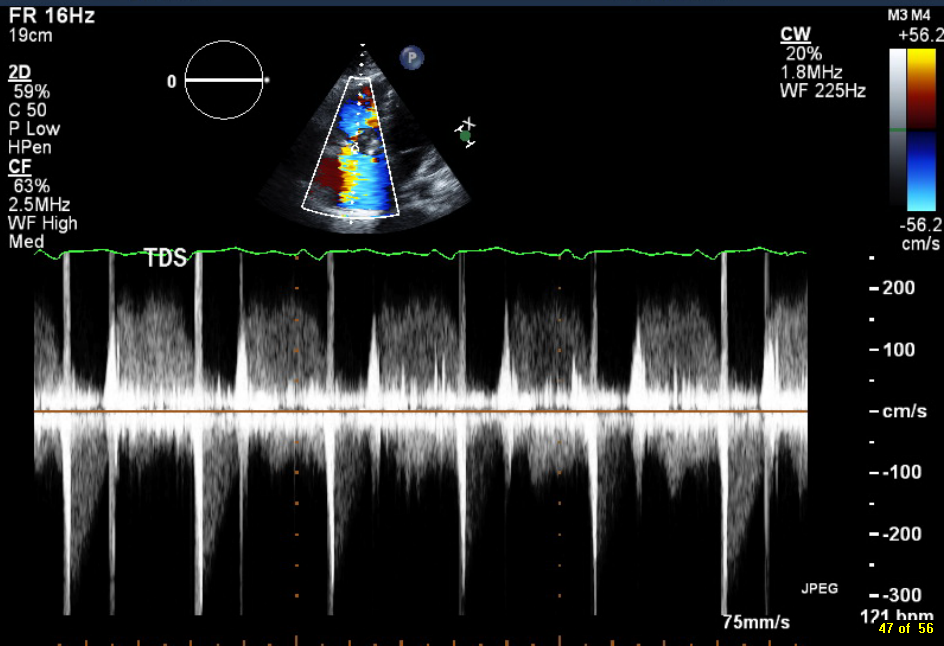

Figure 1. Continuous-wave Doppler tracing through the tricuspid valve.

What tricuspid pathology do the following videos and images demonstrate? (Click on the correct answer to proceed an explanation and discussion)

Cite as: Mansfield W, Boivin M. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: unchain my heart. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2017;14(2):60-4. doi: http://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc013-17 PDF

June 2016 Critical Care Case of the Month

Theodore Loftsgard APRN, ACNP

Julia Terk PA-C

Lauren Trapp PA-C

Bhargavi Gali MD

Department of Anesthesiology

Mayo Clinic Minnesota

Rochester, MN USA

Critical Care Case of the Month CME Information

Members of the Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and California Thoracic Societies and the Mayo Clinic are able to receive 0.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ for each case they complete. Completion of an evaluation form is required to receive credit and a link is provided on the last panel of the activity.

0.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™

Estimated time to complete this activity: 0.25 hours

Lead Author(s): Theodore Loftsgard, APRN, ACNP. All Faculty, CME Planning Committee Members, and the CME Office Reviewers have disclosed that they do not have any relevant financial relationships with commercial interests that would constitute a conflict of interest concerning this CME activity.

Learning Objectives:

As a result of this activity I will be better able to:

- Correctly interpret and identify clinical practices supported by the highest quality available evidence.

- Will be better able to establsh the optimal evaluation leading to a correct diagnosis for patients with pulmonary, critical care and sleep disorders.

- Will improve the translation of the most current clinical information into the delivery of high quality care for patients.

- Will integrate new treatment options in discussing available treatment alternatives for patients with pulmonary, critical care and sleep related disorders.

Learning Format: Case-based, interactive online course, including mandatory assessment questions (number of questions varies by case). Please also read the Technical Requirements.

CME Sponsor: University of Arizona College of Medicine

Current Approval Period: January 1, 2015-December 31, 2016

Financial Support Received: None

History of Present Illness

A 64-year-old man underwent three vessel coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). His intraoperative and postoperative course was remarkable other than transient atrial fibrillation postoperatively for which he was anticoagulated and incisional chest pain which was treated with ibuprofen. He was discharged on post-operative day 5. However, he presented to an outside emergency department two days later with chest pain which had been present since discharge but had intensified.

PMH, SH, and FH

He had the following past medical problems noted:

- Coronary artery disease

- Coronary artery aneurysm and thrombus of the left circumflex artery

- Dyslipidemia

- Hypertension

- Obstructive sleep apnea, on CPAP

- Prostate cancer, status post radical prostatectomy penile prosthesis

He had been a heavy cigarette smoker but had recently quit. Family history was noncontributory.

Physical Examination

His physical examination was unremarkable at that time other than changes consistent with his recent CABG.

Which of the following are appropriate at this time? (Click on the correct answer to proceed to the second of four panels)

Cite as: Loftsgard T, Terk J, Trapp L, Gali B. June 2016 critical care case of the month. Southwest J Pulm Criti Care. 2016 Jun:12(6):212-5. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc043-16 PDF

June 2015 Critical Care Case of the Month: Just Ask the Nurse

Robert A. Raschke, MD

Banner University Medical Center

Phoenix, AZ

History of Present Illness

A 61-year-old police officer had just finished delivering a speech at a law enforcement conference in Phoenix when he briefly complained of chest pain or chest tingling before lapsing into a mute state. He became diaphoretic cyanotic, and vomited. Emergency medical services was called. They noted a blood pressure of 80/50 mm Hg, a pulse of 45, temperature of 95º F, a respiratory rate of 12, and widely dilated pupils. He was transported to the emergency room.

PMH, SH, FH, Medications

Unknown.

Physical Examination

Vital signs: blood pressure 120/75 mm Hg by oscillometric thigh cuff, pulse 43 and irregular, temperature 96º F, respiratory rate 10, SpO2 96% on O2 @ 5L/min by nasal cannula

Neck: No JVD.

Lungs: Poor inspiratory effort

Heart: Irregular rhythm without a murmur

Neurological:

- Delirious – mute – won’t obey commands or track with his eyes

- Pupils 3 mm reactive

- Withdrew 3 extremities to nail bed pressure – he will defend his left arm with his right arm

He suddenly became asystolic and cardiopulmonary resuscitation was begun. After about a minute a femoral pulse could be felt.

Which of the following are indicated at this time? (Click on the correct answer to proceed to the second of five panels)

Reference as: Raschke RA. June 2015 critical care case of the month: just ask the nurse. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2015;10(6):323-9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc077-15 PDF

November 2014 Critical Care Case of the Month: I Be Gaining on My Addiction

Nathaniel R. Little, MD

Carolyn H. Welsh, MD

University of Colorado and the Eastern Colorado Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Department of Medicine

Division of Pulmonary Sciences and Critical Care Medicine

Denver, CO

History of Present Illness

A 33 year-old man came by ambulance to the Emergency Department for progressive altered mental status and bizarre behavior. Per history from his significant other, the patient had a long-standing history of heroin addiction and diazepam abuse. Despite multiple failed attempts at prior detoxification, he had recently resolved to “take matters into his own hands.”