Critical Care

The Southwest Journal of Pulmonary and Critical Care publishes articles directed to those who treat patients in the ICU, CCU and SICU including chest physicians, surgeons, pediatricians, pharmacists/pharmacologists, anesthesiologists, critical care nurses, and other healthcare professionals. Manuscripts may be either basic or clinical original investigations or review articles. Potential authors of review articles are encouraged to contact the editors before submission, however, unsolicited review articles will be considered.

A Case of Brugada Phenocopy in Adrenal Insufficiency-Related Pericarditis

Andrew Kim DO

Cristian Valdez DO

Tony Alarcon MD

Elizabeth Benge MD

Blerina Asllanaj MD

MountainView Hospital

Las Vegas, NV USA

Abstract

This is a report of a 27-year-old male with known history of Addison’s disease, noncompliant with medications, and hypothyroidism who presented with shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, fever, and chest pain as well as Brugada sign seen on electrocardiogram. Echocardiogram revealed a moderate pericardial effusion and laboratory findings were suggestive of adrenal insufficiency. Patient was determined to have Type I Brugada phenocopy, which is a Brugada sign seen on EKG with a reversible cause. In this instance, the Brugada phenocopy was caused by adrenal insufficiency with associated pericarditis. Treatment with high-dose steroids led to resolution of both the pericardial effusion and Brugada sign, providing further evidence of Brugada phenocopy.

Keywords: Brugada Phenocopy, Adrenal insufficiency, Pericarditis, Brugada Sign

Case Presentation

History of Present Illness

A 27-year-old man was admitted for left-sided chest pain. Electrocardiogram (EKG) taken in the emergency department showed suspicious Brugada’s sign in leads V2 and V3 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Initial EKG showing rhythm with signs of inferior infarct based on findings of leads II, II aVL. There are also signs of anterolateral injury seen in leads V2-V5. Also, there were coved ST elevation in leads V2 and V3, suggesting a Type I Brugada sign. (Click here to open Figure 1 in an enlarged, separate window)

He had been feeling short of breath, nauseous, had multiple episodes of vomiting without blood, fever of up to 102 F, and chills for five days prior to admission that had resolved. He described the pain as similar to a “pulled muscle” over his left pectoral area that was worse with extension of the left shoulder as well as with deep inhalation. He denied palpitations, diaphoresis, or radiation of the pain. He denied any family history of cardiac disease or sudden cardiac deaths. Patient lives in San Francisco and travels to Las Vegas periodically to see his family. He had been in Las Vegas for four months prior to admission. He works as a video editor from home. He denies intravenous drug use, history of sexually transmitted illnesses, or history of unsafe sexual activity.

Upon admission, his vitals were: Temp 36.2° C, BP 97/66, HR 84, respiratory rate 16, and SpO2 94% on room air. The patient was slightly hyponatremic with sodium level 131. Potassium levels were also low at 3.2. Physical exam was unremarkable with benign cardiac and respiratory findings. Chest X-ray showed small left-sided pleural effusion with surrounding area of atelectasis. The right lung was unremarkable. In light of the patient’s symptoms and abnormal EKG, an echocardiogram was planned to assess cardiac function and further lab studies were ordered.

Past Medical History

The patient was diagnosed with Addison’s disease at a young age and started on hydrocortisone 5mg daily. Patient also has a history of hypothyroidism and takes levothyroxine 50 mcg daily. Patient has a history of psoriatic arthritis and was taking methotrexate before switching to injectables. Of note, the patient states that he is noncompliant with his oral hydrocortisone 5 mg, sometimes missing multiple days at a time. He had missed three to four days of medication before symptom onset, and had been taking stress doses of 20 mg a day for five days. Given the patient’s presentation and reproducible pain with movement of the left arm, initial differentials included left pectoral strain and community acquired pneumonia. Adrenal insufficiency and autoimmune pericarditis were also considered based on the patient’s history of autoimmune disorders.

Investigation

On day two of hospitalization, the patient continued to be hypotensive and febrile. Cortisol levels were found to be 1.02 mcg/dL, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) less than 1.5 ug/mL, TSH was 1.65 mcg/mL and T4 was 1.67 ng/dL. Urinalysis showed protein, a small amount of ketones, blood, nitrites, 0-2 red blood cells, 10-20 white blood cells, and 5-10 epithelial cells but was negative for leukocyte esterase and bacteria. Inpatient echocardiogram done on day two of hospitalization demonstrated a small to moderate pericardial effusion that appears complex with possible calcifications of visceral pericardium at the right ventricular apex (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Echocardiogram. A: shows a pericardial effusion lateral to the left atrium, 1.20 centimeters in diameter. B: shows a pericardial effusion at the apex of the right ventricle, 1.24 centimeters in diameter. (Click here to open Figure 2 in an enlarged, separate window)

Immunologic work-up was also completed and demonstrated high complement C3 at 187 mg/dL. Viral work-up was also negative. Further investigation of history revealed that the patient had experienced similar symptoms in the past - shortness of breath, fever, nausea - especially during stressful times in his life, but attributed it to anxiety.

Management

Patient was immediately started on intravenous hydrocortisone 50mg every 6 hours after cortisol labs were returned, with the plan to wean to twice a day on the next day and then switching to oral hydrocortisone 20 mg daily. The patient was also started on ceftriaxone 1 gram daily for possible urinary tract infection and doxycycline 100mg twice a day. He complained of dizziness and weakness after switching to oral hydrocortisone, and the dosage was increased to 25 mg daily. The patient stated that after the increase in steroids these symptoms resolved and he had increased energy. His blood pressure remained stable with no episodes of hypotension after switching to oral steroids and his electrolyte panel remained within normal limits.

Follow-up echocardiogram on day five of hospital stay demonstrated a trivial pericardial effusion that had decreased significantly in comparison to the previous study (Figure 3). Repeat electrocardiogram demonstrated normal sinus rhythm with no Brugada sign (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Slight pericardial effusion lateral to the right ventricle, 0.6 centimeters in diameter. Note that there is marked decrease in fluid along the left atrium and apex of the right ventricle compared to Figure 2. (Click here to open Figure 3 in an enlarged, separate window)

Figure 4. Electrocardiogram taken after steroid treatment prior to discharge. Normal sinus rhythm seen in results. Also note normalization in leads V2 and V3 with no clear Brugada seen. (Click here to open Figure 4 in an enlarged, separate window)

Discussion

Our patient’s presentation of shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, fever, and chest pain with negative viral work-up is suggestive of early stages of adrenal insufficiency crisis. Our diagnosis is further evidenced by the patient’s noncompliance with his home steroid doses as well as a morning cortisol level of 1.02 mcg/dL and ACTH less than 1.5 ug/mL. There have been reported cases of adrenal insufficiency causing Type I Brugada phenocopy and normalization with treatment (1). The normalization of our patient’s EKG and pericarditis after treatment with high dose steroids is evidence of Brugada phenocopy in this case. In addition, pericarditis has been shown to present as a Type 1 Brugada phenocopy (BrP), a Brugada sign seen on EKG with a reversible cause (2).

One common cause of BrP is electrolyte abnormalities, as BrP can be seen in patients with profound hyponatremia and hyperkalemia (3,4). In particular, hyperkalemia is a common culprit of Brugada sign on EKG as potassium excess can decrease the resting membrane potential (5). Typically, patients with adrenal insufficiency will exhibit electrolyte abnormalities that can explain Brugada sign on EKG. This patient’s electrolytes were indicative of hyponatremia and hypokalemia upon presentation. Although the electrolyte abnormalities were mild, the hyponatremia in particular contributed to the team’s initial suspicion of adrenal insufficiency. To our knowledge, this is the first instance of Brugada sign and pericarditis seen together in adrenal insufficiency crisis. Cases of Brugada pattern in adrenal crisis have been reported (6), however no echocardiogram was done in these case reports.

In addition, reported cases of pericarditis caused by Brugada phenocopy offers an alternative view of the sequence of events in this patient (7). Pericardial disease is known to cause Brugada phenocopy, and this may have been the case in our patient. Both pericarditis and BrP can be caused by adrenal insufficiency, so it is also possible that both of these events were independent of each other and stem from the underlying adrenal insufficiency. As such, this case highlights an important point mentioned in the previous case reports: the need to consider both pericarditis and adrenal insufficiency crisis in a patient presenting with Brugada phenocopy.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in patients presenting with Brugada sign the possibility of adrenal insufficiency crisis as well as pericarditis should be considered, especially in patients with known Addison’s disease. Furthermore, patients presenting with Brugada sign with no history of genetic cardiac history or family history of sudden cardiac death should be evaluated for other causes, such as adrenal insufficiency or pericarditis.

References

- Anselm DD, Evans JM, Baranchuk A. Brugada phenocopy: A new electrocardiogram phenomenon. World J Cardiol. 2014 Mar 26;6(3):81-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti M, Olivi G, Francavilla F, Borgognoni F. Pericarditis mimicking Brugada syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2017 Apr;35(4):669.e1-669.e3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunuk A, Hunuk B, Kusken O, Onur OE. Brugada Phenocopy Induced by Electrolyte Disorder: A Transient Electrocardiographic Sign. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2016 Jul;21(4):429-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manthri S, Bandaru S, Ibrahim A, Mamillapalli CK. Acute Pericarditis as a Presentation of Adrenal Insufficiency. Cureus. 2018 Apr 13;10(4):e2474. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan GX, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for the Brugada syndrome and other mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis associated with ST-segment elevation. Circulation. 1999 Oct 12;100(15):1660-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iorgoveanu C, Zaghloul A, Desai A, Balakumaran K, Adeel MY. A Case of Brugada Pattern Associated with Adrenal Insufficiency. Cureus. 2018 Jun 6;10(6):e2752. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehadeh M, O'Donoghue S. Acute Pericarditis-Induced Brugada Phenocopy: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Cureus. 2020 Aug 15;12(8):e9761. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Cite as: Kim A, Valdez C, Alarcon T, Benge E, Asllanaj B. A Case of Brugada Phenocopy in Adrenal Insufficiency-Related Pericarditis. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care Sleep. 2022;25(2):25-29. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpccs033-22 PDF

MSSA Pericarditis in a Patient with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Flare

Antonious Anis MD

Marian Varda DO

Ahmed Dudar MD

Evan D. Schmitz MD

Saint Mary Medical Center

Long Beach, CA 90813

Abstract

Bacterial pericarditis is a rare yet fatal form of pericarditis. With the introduction of antibiotics, incidence of bacterial pericarditis has declined to 1 in 18,000 hospitalized patients. In this report, we present a rare case of MSSA pericarditis in a patient that presented with systemic lupus erythematosus flare, which required treatment with antibiotics and source control with pericardial window and drain placement.

Abbreviations

- ANA: Anti-nuclear Antibody

- Anti-dsDNA: Anti double stranded DNA

- IV: intravenous

- MSSA: Methicillin-sensitive staphylococcus aureus

- SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus

- TTE: Transthoracic Echocardiogram

Case Presentation

History of Present Illness

31-year-old female with history of SLE, hypertension and type 1 diabetes mellitus presented with several days of pleuritic chest pain.

Physical Examination

Vitals were notable for blood pressure 204/130. She had normal S1/S2 without murmurs and had trace bilateral lower extremity edema.

Laboratory and radiology

Admission labs were notable for creatinine of 1.8, low C3 and C4 levels, elevated anti-smith, anti-ds DNA and ANA titers. ESR was elevated at 62. Troponin was normal on 3 separate samples 6 hours apart. CT Angiography of the chest showed moderate pericardial effusion (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CT Angiography of the chest on admission with moderate pericardial effusion (arrows).

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed a moderate effusion, but no tamponade physiology.

Hospital Course

Given the ongoing lupus flare, pleuritic chest pain, elevated ESR, normal troponin and pericardial effusion, the patient’s chest pain was thought to be caused by acute pericarditis secondary to SLE flare. The patient was treated with anti-hypertensives, though her creatinine worsened, which prompted a kidney biopsy, that showed signs of lupus nephritis. The patient was treated with methylprednisolone pulse 0.5 mg/kg for three days, then prednisone taper. Her home hydroxychloroquine regimen was resumed. The patient became febrile on hospital day 15 and blood cultures were obtained. These later revealed MSSA bacteremia, which is thought to be secondary to thrombophlebitis from an infected peripheral IV line in her left antecubital fossa. On hospital day 16, the patient complained of worsening chest pain and had an elevated troponin of 2, but no signs of ischemia on EKG. Repeat echo was performed, which showed increase in size of the pericardial effusion and right ventricular collapse during diastole, concerning for impending tamponade (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Video of the transthoracic echocardiography showing a pericardial effusion (top arrow) with RV collapse during diastole (bottom arrow), concerning for impending cardiac tamponade.

The patient remained hemodynamically stable. Pericardial window was performed. 500 cc of purulent fluid was drained, and a pericardial drain was placed. Intra-operative fluid culture grew MSSA. The drain was left in place for 13 days. The patient was treated with a 4-week course of oxacillin. Blood cultures obtained on hospital day 28 were negative. A repeat echo was normal. The patient was discharged without further complications.

Discussion

Bacterial pericarditis is a rare, but fatal infection, with 100% mortality in untreated patients (1). After the introduction of antibiotics, the incidence of bacterial pericarditis declined to 1 in 18,000 hospitalized patients, from 1 in 254 (2). The most implicated organisms are Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Hemophilus and M. tuberculosis (3). Historically, pneumonia was the most common underlying infection leading to purulent pericarditis, especially in the pre-antibiotic era (2). Since the widespread use of antibiotics, purulent pericarditis has been linked to bacteremia, thoracic surgery, immunosuppression, and malignancy (3).

Acute pericarditis is a common complication in SLE with incidence of 11-54% (4), though few cases of bacterial pericarditis were reported in SLE patients. The organisms in these cases were staphylococcus aureus, Neisseria gonorrhea and mycobacterium tuberculosis (5). Despite these reports, acute pericarditis secondary to immune complex mediated inflammatory process remains a much more common cause of pericarditis than bacterial pericarditis in SLE (6). There’s minimal data to determine whether the incidence of bacterial pericarditis in patients with SLE is increased compared to the general population; however, there is a hypothetically increased risk for purulent pericarditis in SLE given the requirement for immunosuppression. Disease activity is yet another risk factor for bacterial infections in SLE, which is thought to be a sequalae of treatment with high doses of steroids (7). In this case, the patient had an SLE flare on presentation with SLEDAI-2K score of 13. Both immunosuppression and bacteremia may have precipitated this patient’s infection with bacterial pericarditis.

Diagnosis of bacterial pericarditis requires high index of suspicion, as other etiologies of pericarditis are far more common. In this case, we initially attributed the patient’s pericarditis to her SLE flare. The patient’s fever on hospital day 15 prompted the infectious work up. MSSA pericarditis was diagnosed later after the pericardial fluid culture grew MSSA. Delay in the diagnosis can be detrimental as patients may progress rapidly to cardiac tamponade.

Treatment requires surgical drainage for source control along with antibiotics (8). In our case, the patient required pericardial window and placement of a drain for 13 days. In bacterial pericarditis, the purulent fluid tends to re-accumulate; therefore, subxiphoid pericardiostomy and complete drainage is recommended (8). In some cases, intrapericardial thrombolysis therapy may be required if adhesions develop (8). With appropriate source control and antibiotics therapy, survival rate is up to 85% (8).

Conclusion

Bacterial pericarditis is a rare infection in the antibiotic era, though some patients remain at risk for acquiring it. Despite the high mortality rate, patients can have good outcomes if bacterial pericarditis is recognized early and treated.

References

- Kaye A, Peters GA, Joseph JW, Wong ML. Purulent bacterial pericarditis from Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Case Rep. 2019 May 28;7(7):1331-1334. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh SV, Memon N, Echols M, Shah J, McGuire DK, Keeley EC. Purulent pericarditis: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009 Jan;88(1):52-65. [CrossRef] [PubMed}

- Kondapi D, Markabawi D, Chu A, Gambhir HS. Staphylococcal Pericarditis Causing Pericardial Tamponade and Concurrent Empyema. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2019 Jul 18;2019:3701576. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dein E, Douglas H, Petri M, Law G, Timlin H. Pericarditis in Lupus. Cureus. 2019 Mar 1;11(3):e4166. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coe MD, Hamer DH, Levy CS, Milner MR, Nam MH, Barth WF. Gonococcal pericarditis with tamponade in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1990 Sep;33(9):1438-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buppajamrntham T, Palavutitotai N, Katchamart W. Clinical manifestation, diagnosis, management, and treatment outcome of pericarditis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014 Dec;97(12):1234-40. [PubMed]

- Nived O, Sturfelt G, Wollheim F. Systemic lupus erythematosus and infection: a controlled and prospective study including an epidemiological group. Q J Med. 1985 Jun;55(218):271-87. [PubMed]

- Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by: The European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-2964. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

October 2021 Critical Care Case of the Month: Unexpected Post-Operative Shock

Sooraj Kumar MBBS

Benjamin Jarrett MD

Janet Campion MD

University of Arizona College of Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine and Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Tucson, AZ USA

History of Present Illness

A 55-year-old man with a past medical history significant for endocarditis secondary to intravenous drug use, osteomyelitis of the right lower extremity was admitted for ankle debridement. Pre-operative assessment revealed no acute illness complaints and no significant findings on physical examination except for the ongoing right lower extremity wound. He did well during the approximate one-hour “incision and drainage of the right lower extremity wound”, but became severely hypotensive just after the removal of the tourniquet placed on his right lower extremity. Soon thereafter he experienced pulseless electrical activity (PEA) cardiac arrest and was intubated with return of spontaneous circulation being achieved rapidly after the addition of vasopressors. He remained intubated and on pressors when transferred to the intensive care unit for further management.

PMH, PSH, SH, and FH

- S/P Right lower extremity incision and drainage for suspected osteomyelitis as above

- Distant history of endocarditis related to IVDA

- Not taking any prescription medications

- Current smoker, occasional alcohol use

- Former IVDA

- No pertinent family history including heart disease

Physical Exam

- Vitals: 100/60, 86, 16, afebrile, 100% on ACVC 420, 15, 5, 100% FiO2

- Sedated well appearing male, intubated on fentanyl and norepinephrine

- Pupils reactive, nonicteric, no oral lesions or elevated JVP

- CTA, normal chest rise, not overbreathing the ventilator

- Heart: Regular, normal rate, no murmur or rubs

- Abdomen: Soft, nondistended, bowel sounds present

- No left lower extremity edema, right calf dressed with wound vac draining serosanguious fluid, feet warm with palpable pedal pulses

- No cranial nerve abnormality, normal muscle bulk and tone

Clinically, the patient is presenting with post-operative shock with PEA cardiac arrest and has now been resuscitated with 2 liters emergent infusion and norepinephrine at 70 mcg/minute.

What type of shock is most likely with this clinical presentation?

Cite as: Srinivasan S, Kumar S, Jarrett B, Campion J. October 2021 Critical Care Case of the Month: Unexpected Post-Operative Shock. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2021;23(4):93-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc041-21 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Caught in the Act

Uzoamaka Ogbonnah MD1

Isaac Tawil MD2

Trenton C. Wray MD2

Michel Boivin MD1

1Department of Internal Medicine

2Department of Emergency Medicine

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

Albuquerque, NM USA

A 16-year-old man was brought to the Emergency Department via ambulance after a fall from significant height. On arrival to the trauma bay, the patient was found to be comatose and hypotensive with a blood pressure of 72/41 mm/Hg. He was immediately intubated, started on norepinephrine drip with intermittent dosing of phenylephrine, and transfused with 3 units of packed red blood cells. He was subsequently found to have extensive fractures involving the skull and vertebrae at cervical and thoracic levels, multi-compartmental intracranial hemorrhages and dissection of the right cervical internal carotid and vertebral arteries. He was transferred to the intensive care unit for further management of hypoxic respiratory failure, neurogenic shock and severe traumatic brain injury. Following admission, the patient continued to deteriorate and was ultimately declared brain dead 3 days later. The patient’s family opted to make him an organ donor

On ICU day 4, one day after declaration of brain death, while awaiting organ procurement, the patient suddenly developed sudden onset of hypoxemia and hypotension while being ventilated. The patient had a previous trans-esophageal echo (TEE) the day prior (Video 1). A repeat bedside TEE was performed revealing the following image (Video 2).

Video 1. Mid-esophageal four chamber view of the right and left ventricle PRIOR to onset of hypoxemia.

Video 2. Mid-esophageal four chamber view of the right and left ventricle AFTER deterioration.

What is the cause of the patient’s sudden respiratory deterioration? (Click on the correct answer to be directed to an explanation)

- Atrial Myxoma

- Fat emboli syndrome

- Thrombus in-transit and pulmonary emboli

- Tricuspid valve endocarditis

Cite as: Ogbonnah U, Tawil I, Wray TC, Boivin M. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: Caught in the act. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;17(1):36-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc091-18 PDF

January 2018 Critical Care Case of the Month

Theodore Loftsgard, APRN, ACNP

Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care

Mayo Clinic Minnesota

Rochester, MN USA

History of Present Illness

The patient is a 51-year-old woman admitted with a long history of progressive shortness of breath. She has a long history of “heart problems”. She uses supplemental oxygen at 1 LPM by nasal cannula.

Past Medical History, Social History and Family History

She also has several comorbidities including renal failure with two renal transplants and a history of relatively recent RSV and CMV pneumonia. She is a life-long nonsmoker. Her family history is noncontributory.

Physical Examination

- Vital signs: Blood pressure 145/80 mm Hg, heart rate 59 beats/min, respiratory rate 18, T 37.0º C, SpO2 91% of 1 LPM.

- Lungs: Clear.

- Heart: Regular rhythm with G 3/6 systolic ejection murmur at the base.

- Abdomen: unremarkable.

- Extremities: no edema

Which of the following should be performed? (Click on the correct answer to proceed to the second of seven pages)

Cite as: Loftsgard T. January 2018 critical care case of the month. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2018;16(1):1-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc155-17 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Unchain My Heart

William Mansfield, MD

Michel Boivin, MD

Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine

Department of Medicine,

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

Albuquerque, NM USA

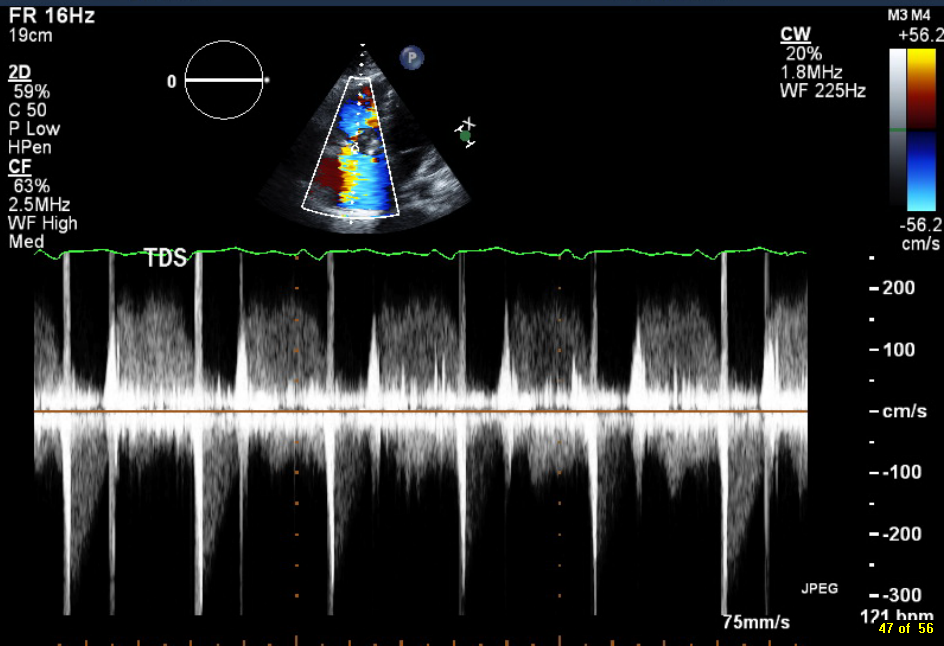

A 46-year-old man presented after a motor vehicle collision. He suffered abdominal injuries (liver laceration, avulsed gall bladder) which were successfully managed non-operatively. The patient remained intubated on mechanical ventilation and remained hypotensive after the injuries resolved. The patient required norepinephrine at low doses to maintain a normal blood pressure. It was noted the patient had a history of remote tricuspid valve replacement. A bedside echocardiogram was then performed to determine the etiology of the patient’s persistent hypotension after hypovolemia had been excluded.

Video 1. Apical four chamber view centered on the right heart.

Video 2. Apical four chamber view centered on the right heart, with color Doppler over the right atrium and ventricle.

Video 3. Right ventricular inflow view.

Figure 1. Continuous-wave Doppler tracing through the tricuspid valve.

What tricuspid pathology do the following videos and images demonstrate? (Click on the correct answer to proceed an explanation and discussion)

Cite as: Mansfield W, Boivin M. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: unchain my heart. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2017;14(2):60-4. doi: http://doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc013-17 PDF

June 2016 Critical Care Case of the Month

Theodore Loftsgard APRN, ACNP

Julia Terk PA-C

Lauren Trapp PA-C

Bhargavi Gali MD

Department of Anesthesiology

Mayo Clinic Minnesota

Rochester, MN USA

Critical Care Case of the Month CME Information

Members of the Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and California Thoracic Societies and the Mayo Clinic are able to receive 0.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ for each case they complete. Completion of an evaluation form is required to receive credit and a link is provided on the last panel of the activity.

0.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™

Estimated time to complete this activity: 0.25 hours

Lead Author(s): Theodore Loftsgard, APRN, ACNP. All Faculty, CME Planning Committee Members, and the CME Office Reviewers have disclosed that they do not have any relevant financial relationships with commercial interests that would constitute a conflict of interest concerning this CME activity.

Learning Objectives:

As a result of this activity I will be better able to:

- Correctly interpret and identify clinical practices supported by the highest quality available evidence.

- Will be better able to establsh the optimal evaluation leading to a correct diagnosis for patients with pulmonary, critical care and sleep disorders.

- Will improve the translation of the most current clinical information into the delivery of high quality care for patients.

- Will integrate new treatment options in discussing available treatment alternatives for patients with pulmonary, critical care and sleep related disorders.

Learning Format: Case-based, interactive online course, including mandatory assessment questions (number of questions varies by case). Please also read the Technical Requirements.

CME Sponsor: University of Arizona College of Medicine

Current Approval Period: January 1, 2015-December 31, 2016

Financial Support Received: None

History of Present Illness

A 64-year-old man underwent three vessel coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). His intraoperative and postoperative course was remarkable other than transient atrial fibrillation postoperatively for which he was anticoagulated and incisional chest pain which was treated with ibuprofen. He was discharged on post-operative day 5. However, he presented to an outside emergency department two days later with chest pain which had been present since discharge but had intensified.

PMH, SH, and FH

He had the following past medical problems noted:

- Coronary artery disease

- Coronary artery aneurysm and thrombus of the left circumflex artery

- Dyslipidemia

- Hypertension

- Obstructive sleep apnea, on CPAP

- Prostate cancer, status post radical prostatectomy penile prosthesis

He had been a heavy cigarette smoker but had recently quit. Family history was noncontributory.

Physical Examination

His physical examination was unremarkable at that time other than changes consistent with his recent CABG.

Which of the following are appropriate at this time? (Click on the correct answer to proceed to the second of four panels)

Cite as: Loftsgard T, Terk J, Trapp L, Gali B. June 2016 critical care case of the month. Southwest J Pulm Criti Care. 2016 Jun:12(6):212-5. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc043-16 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Two’s a Crowd

A 43 year old previously healthy woman was transferred to our hospital with refractory hypoxemia secondary to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) due to H1N1 influenza. She had presented to the outside hospital one week prior with cough and fevers. Chest radiography and computerized tomography of the chest revealed bilateral airspace opacities due to dependent consolidation and bilateral ground glass opacities. A transthoracic echocardiogram at the time of the patient’s admission was reported as not revealing any significant abnormalities.

At the outside hospital she was placed on mechanical ventilation with low tidal volume, high Positive end-expiratory pressure (20 cm H20), and a Fraction of inspired Oxygen (FiO2) of 1.0. Paralysis was later employed without significant improvement.

Upon arrival to our hospital, patient was severely hypoxemic with partial pressure of oxygen / FiO2 (P/F) ratio of 43. She was paralyzed with cis-atracurium and placed on airway pressure release ventilation (APRV) with the following settings (pressure high 28 cm H2O, pressure low 0 cm H2O, time high 5.5 sec, time low 0.5 sec). The patient remained severely hypoxemic with on oxygen saturation in the high 70 percent range.

A bedside echocardiogram was performed (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Subcostal long axis echocardiogram.

Figure 2. Subcostal short axis echocardiogram

What abnormality is demonstrated by the short and long axis subcostal views? (Click on the correct answer for an explanation)

Cite as: Abukhalaf J, Boivin M. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: two's a crowd. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2016 Mar;12(3):104-7. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc028-16 PDF

March 2016 Critical Care Case of the Month

Theo Loftsgard APRN, ACNP

Joel Hammill APRN, CNP

Mayo Clinic Minnesota

Rochester, MN USA

Critical Care Case of the Month CME Information

Members of the Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and California Thoracic Societies and the Mayo Clinic are able to receive 0.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ for each case they complete. Completion of an evaluation form is required to receive credit and a link is provided on the last panel of the activity.

0.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™

Estimated time to complete this activity: 0.25 hours

Lead Author(s): Theo Loftsgard APRN, ACNP. All Faculty, CME Planning Committee Members, and the CME Office Reviewers have disclosed that they do not have any relevant financial relationships with commercial interests that would constitute a conflict of interest concerning this CME activity.

Learning Objectives:

As a result of this activity I will be better able to:

- Correctly interpret and identify clinical practices supported by the highest quality available evidence.

- Will be better able to establsh the optimal evaluation leading to a correct diagnosis for patients with pulmonary, critical care and sleep disorders.

- Will improve the translation of the most current clinical information into the delivery of high quality care for patients.

- Will integrate new treatment options in discussing available treatment alternatives for patients with pulmonary, critical care and sleep related disorders.

Learning Format: Case-based, interactive online course, including mandatory assessment questions (number of questions varies by case). Please also read the Technical Requirements.

CME Sponsor: University of Arizona College of Medicine

Current Approval Period: January 1, 2015-December 31, 2016

Financial Support Received: None

History of Present Illness

A 58-year-old man was admitted to the ICU in stable condition after an aortic valve replacement with a mechanical valve.

Past Medical History

He had with past medical history significant for endocarditis, severe aortic regurgitation related to aortic valve perforation, mild to moderate mitral valve regurgitation, atrial fibrillation, depression, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and previous cervical spine surgery. As part of his preop workup, he had a cardiac catheterization performed which showed no significant coronary artery disease. Pulmonary function tests showed an FEV1 of 55% predicted and a FEV1/FVC ratio of 65% consistent with moderate obstruction.

Medications

Amiodarone 400 mg bid, digoxin 250 mcg, furosemide 20 mg IV bid, metoprolol 12.5 mg bid. Heparin nomogram since arrival in the ICU.

Physical Examination

He was extubated shortly after arrival in the ICU. Vitals signs were stable. His weight had increased 3 Kg compared to admission. He was awake and alert. Cardiac rhythm was irregular. Lungs had decreased breath sounds. Abdomen was unremarkable.

Laboratory

His admission laboratory is unremarkable and include a creatinine of 1.0 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) of 18 mg/dL, white blood count (WBC) of 7.3 X 109 cells/L, and electrolytes with normal limits.

Radiography

His portable chest x-ray is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Portable chest x-ray taken on admission to the ICU.

What should be done next? (Click on the correct answer to proceed to the second of five panels)

- Bedside echocardiogram

- Diuresis with a furosemide drip because of his weight gain and cardiomegaly

- Observation

- 1 and 3

- All of the above

Cite as: Loftsgard T, Hammill J. March 2016 critical care case of the month. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2016;12(3):81-8. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc018-16 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Hungry Heart

A 31-year-old incarcerated man with a past medical history of intravenous drug use and hepatitis C, presented with a one week history of dry, non-productive cough, orthopnea and exertional dyspnea. He denied current intravenous drug use, and endorsed that the last time he used was before he was incarcerated over 3 years ago, his last tattoo was in prison, 6 months prior. He was found to have an oxygen saturation of 77% on room air, fever of 40º C, heart rate of 114 bpm, and blood pressure of 80/50 mmHg. The patient had a leukocytosis of 14 x109/L, and a chest x-ray demonstrating patchy airspace disease. Blood cultures were sent and he was treated with antibiotics and vasopressors for septic shock. The patient was intubated for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to multifocal pneumonia. A bedside transthoracic echocardiogram was performed.

Figure 1. Apical four chamber view echocardiogram with color Doppler over the mitral valve.

Figure 2. Right Ventricular (RV) inflow view echocardiogram from same patient What is the likely diagnosis supported by the echocardiogram? (Click on the correct answer for an explanation)

Cite as: Villalobos N, Stoltze K, Azeem M. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: hungry heart. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2016;12(1):24-7. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc007-16 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Now My Heart Is Even More Full

Bilal Jalil, MD

Michel Boivin, MD

Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

Albuquerque, NM

A 49-year-old man with type 2 diabetes, intravenous drug abuse and heart failure presented to the emergency room with 2 weeks of progressively worsening chest pain, lower extremity swelling and shortness of breath. The patient was found to have an elevated troponin as well as brain natriuretic peptide and the absence of ischemic electrocardiogram findings. The patient was admitted to the medical ICU for hypoxic respiratory failure and shock of uncertain etiology. Clinically he seemed to be in decompensated heart failure and a bedside echocardiogram was performed (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Parasternal short axis view at the level of the aortic valve

Figure 2. Apical 4 chamber view.

What is the best explanation for the echocardiographic findings shown above? (Click on the correct answer for the explanation)

Reference as: Jalil B, Boivin M. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: now my heart is even more full. Souhtwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2015;10(2):83-6. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc020-15 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Now My Heart Is Full

Sapna Bhatia M.D.

Rodrigo Vazquez-Guillamet M.D.

Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

Albuquerque, NM

A 65 year old woman with a history of hypertension and a recent diagnosis of multiple myeloma was admitted to the ICU with septic shock due to Morganella morganii bacteremia. She was treated with cefepime, levophed and dobutamine. During treatment she developed symptoms and a chest x-ray compatible with congestive heart failure. A transthoracic echo is shown below (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Parasternal long echocardiogram of the patient.

Figure 2. Apical four-chamber echocardiogram of the patient.

Additionally a spectral pulsed-wave Doppler study of the mitral inflow velocities is presented (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Pulsed-wave spectral Doppler velocities of the mitral-valve inflow of the patient.

What is the best explanation for the findings seen in on the echocardiogram? (Click on the correct answer to proceed to the next panel and explanation)

Reference as: Bhatia S, Vazquez-Guillamet R. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: now my heart is full. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2014;9(5):291-4. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc154-14 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: A Tempting Dilemma

Issam Marzouk MD

Lana Melendres MD

Michel Boivin MD

Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep

Department of Medicine

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

MSC 10-5550

Albuquerque, NM 87131 USA

A 46 year old woman presented with progressive severe hypoxemia and a chronic appearing pulmonary embolus on chest CT angiogram to the intensive care unit. The patient was hemodynamically stable, but had an oxygen saturation of 86% on a high-flow 100% oxygen mask. The patient had been previously investigated for interstitial lung disease over the past 2 year, this was felt to be due to non-specific interstitial pneumonitis. Her echocardiogram findings are as presented below (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Parasternal long axis view. Upper panel: static image. Lower panel: video.

Figure 2. Apical four chamber view. Upper panel: static image. Lower panel: video

The patient had refractory hypoxemia despite trials of high flow oxygen and non-invasive positive pressure ventilation. She had mild symptoms at rest but experienced severe activity intolerance secondary to exertional dyspnea. Vitals including blood pressure remained stable and normal during admission and the patient had a pulsus paradoxus measurement of < 10 mmHg. She had previously had an echocardiogram 6 months before that revealed significant pulmonary hypertension.

What would be the most appropriate next step regarding management of her echocardiogram findings? (click on the correct answer to move to the next panel)

Reference as: Marzouk I, Melendres L, Boivin M. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: a tempting dilemma. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2014;9(3):193-6. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc128-14 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Cardiogenic Shock-This Is Not a Drill

Ramakrishna Chaikalam, MD

Shozab Ahmed, MD

Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep

University of New Mexico

Albuquerque, NM

A 45-year-old woman with no significant past history developed gradual onset of shortness of breath and cough over 1 week. She presented to the emergency department. Her initial chest x-ray showed an enlarged heart and bilateral pulmonary edema. The patient became progressively hypotensive and hypoxic and was intubated. Transthoracic echocardiography is shown below (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Transthoracic echocardiogram in the para-sternal long axis view of the heart.

What intra-cardiac device in the left ventricle is pictured on the image? (Click on the correct answer to proceed to the next panel)

- Amplatz closure device of atrial septal defect

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenator (ECMO) cannula

- Impella device

- Intra-aortic balloon pump

- Pacemaker lead

Reference as: Chaikalam R, Ahmed S. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: cardiogenic shock-this is not a drill. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2014;9(1):27-9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc091-14 PDF

Fat Embolism Syndrome: Improved Diagnosis Through the Use of Bedside Echocardiography

Douglas T. Summerfield, MD

Kelly Cawcutt, MD

Robert Van Demark, MD

Matthew J. Ritter, MD

Departments of Anesthesia and Pulmonary/Critical Care Medicine

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, MN

Case Report

A 77 year old female with a past medical history of dementia, chronic atrial fibrillation requiring anticoagulation, hypertension, biventricular congestive heart failure with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction, pulmonary hypertension, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) presented to the emergency room after she sustained a ground level fall while sitting in a chair. The patient reportedly fell asleep while sitting at the kitchen table, and subsequently fell to her right side. According to witnesses, she did not strike her head, and there was no observed loss of consciousness. As part of her initial evaluation, at an outside hospital, radiographs of the pelvis, hip, and knee were obtained. These identified a definitive right superior pubic ramus fracture with inferior displacement and a questionable fracture of the right femoral neck. Shortly thereafter, the patient was transferred to our hospital for further management. On exam, the patient had a painful right hip limiting active motion and her right lower extremity was neurovascularly intact without paresthesias or dysesthesias. The remainder of the exam was unremarkable. In the emergency room, a repeat radiograph showed no evidence of a right femur fracture. Later in the evening a CT scan of the pelvis with intravenous contrast showed acute fractures through the right superior and inferior pubic rami with associated hematoma. Multiple tiny bony fragments were noted adjacent to the superior pubic ramus fracture (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CT scan demonstrating acute fractures through the superior and inferior pubic rami with associated hematoma. Multiple tiny bone fragments are adjacent to the superior pubic ramus fracture.

The CT did not show an apparent femur fracture. MRI of the pelvis and hip were ordered to assess for a femoral fracture; however this was not obtained secondary to patient confusion thus no quality diagnostic images were produced. The orthopedic service concluded that surgery was not required for the stable, type 1 lateral compression injury that resulted from the fall.

The patient was admitted to a general medicine floor for non-surgical management which included weight bearing as tolerated as well as therapy with physical medicine and rehabilitation. On admission, her vital signs were stable, including a heart rate of 89, blood pressure of 159/89, respirations of 20, with the exception of her peripheral oxygen saturation which was 89% on room air. Over the next several hospital days, she continued to have low oxygen saturations, began requiring fluid boluses to maintain an adequate mean arterial blood pressure (secondary to systolic blood pressure falling to the 70-80mmHg range intermittently) and she developed acute kidney injury with her creatinine increasing to 4.2 from her baseline of 1.1. Nephrology was consulted to evaluate the acute kidney injury and their impression was acute renal failure secondary to contrast administration for the initial CT scan, in the setting of chronic spironolactone and furosemide use. The patient’s mental status remained altered, her speech although typically understandable was non-coherent, and she remained bed-bound. Due to her underlying dementia, her baseline mental status was difficult to determine and this combined with her opioids for pain control were felt to contribute to her mental status.

During her first dialysis session, the patient developed hypotension and hypoxemia which necessitated a rapid response call and transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU). The impression at the time of transfer to the ICU was septic shock with multi-organ dysfunction syndrome, presumably from a urinary source. The initial exam by the ICU team demonstrated what was thought to be considerable acute mental status change with agitation and moaning, hypotension, hypoxemia, and continued renal failure. Further review of her hospital course revealed that these changes had slowly been progressing since admission. Stabilization in the ICU included placement of a right internal jugular central venous catheter, blood pressure support with vasopressors, as well as intubation and high level of ventilatory support, including inhaled alprostadil, for severe hypoxemic respiratory failure. In addition, she was also placed on continuous renal replacement therapy.

In order to better assess the patient’s fluid status, the service fellow assessed the vena cava with the bedside ultrasound. While observing the collapsibility of the IVC, small hyperechoic spheres were observed traveling through the IVC proximally towards the right heart. A subcostal window focusing on the right ventricle demonstrated the same hyperechoic spheres whirling within the right ventricle. These same spheres were seen in both the four chamber view (Figure 2), as well as the short axis view and were present for several hours.

Figure 2. Four chambered view revealing right ventricular bowing as well as small hyperechoic spheres present in the right ventricle and atria.

Two hours later, a formal bedside echocardiogram was performed to evaluate the right heart structure and function. The estimated right ventricular systolic pressure was at 70 mm Hg, indicating severe pulmonary hypertension. The right ventricle was enlarged, and there was severe tricuspid regurgitation. Again there continued to be small hyperechoic spheres within her right ventricle as well as her right atria. Per the formal cardiologist reading, these were consistent with fat emboli. Further laboratory evaluation, including the presence of urinary fat, helped confirm the diagnosis of fat emboli syndrome.

Supportive care was continued, but without obvious improvement. After a family care conference, she was transitioned to palliative care and died.

Background

Fat emboli (FE) and fat emboli syndrome (FES) have been described clinically and pathologically since the 1860’s. Early work by Zenker in 1862 first described the pathologic significance of fat embolism with the link of fat to bone marrow release during fractures was discovered by Wagner in 1865. Despite the 150 years since its discovery, the diagnosis of Fat Embolism remains elusive. FE is quite common with the presence of intravascular pulmonary fat seen in greater than 90% of patients with skeletal trauma at autopsy (1). However, the presence of pulmonary fat alone does not necessarily mean the patient will develop FES. In a case series of 51 medical and surgical ICU patients, FE was identified in 28 (51%) of patients, none of whom had classic manifestations of FES (2).

The three major components of FES have classically consisted of the triad of petechial rash, progressive respiratory failure, and neurologic deterioration. The incidence following orthopedic procedures ranges from 0.25% to 35% (3). The wide variation of the reported incidence may in part be due to the fact that FES can affect almost every organ system and the classic symptoms are only present either transiently or in varying degrees, and may not manifest for 12-72 hours after the initial insult (4). The patient we present represents both the lack of the classic triad and the delayed onset of signs and symptoms, illustrating the elusiveness of the diagnosis.

Of the major clinical criteria, the cardio-pulmonary symptoms are the most clinically significant. Symptoms occur in up to 75% of patients with FES and range from mild hypoxemia to ARDS and/or acute cor pulmonale. The timing of symptoms may coincide with manipulation of a fracture, and there have been numerous reports of this occurring intraoperatively with direct visualization of fat emboli seen on trans-esophageal echo (TEE) (5-8).

The classic petechial rash, which was not noted in our patient, is typically seen on the upper anterior torso, oral mucosa, and conjunctiva. It is usually resolved within 24 hours and has been attributed to dermal vessel engorgement, endothelial fragility, and platelet damage all from the release of free fatty acids (9). The clinical manifestation of this “classic” finding varies widely and has been reported in 25-95% of the cases (4, 10).

Neurologic dysfunction can range from headache to seizure and coma and is thought to be secondary to cerebral edema due to multifactorial insults. These neurologic changes are seen in up to 86% of patients, and on MRI produce multiple small, non-confluent hyper intensities that appear within 30 minutes of injury. The number and size correlate to GCS, and subsequently reversal of the lesions is seen during neurologic recovery. (11,12).

Temporary CNS dysfunction usually occurs 24-72 hours after initial injury and acute loss of consciousness immediately post-operatively has been documented. Of note, this loss of consciousness may not be a catastrophic event. In a case report by Nandi et al., a patient with acute loss of consciousness made full neurologic recovery within four hours (13). In the retina, direct evidence of FE and FES manifests as cotton-wool spots and flame-like hemorrhages (1). However these findings are only detected in 50% of patient with FES (14)

FES also affects the hematological system, producing anemia and thrombocytopenia 37% and 67% of the time, respectively (15, 16). Thrombocytopenia is correlated to an increased A-a gradient, which Akhtar et al. noted that some clinicians include this finding in the criteria to diagnose FES (1).

Diagnosis

Given the broad and varying manifestations of FES, others have broadened the criteria. The Lindeque criteria require a femur fracture. The FES Index is a scoring system which includes vitals, radiographic findings, and blood gas results. Weisz and colleagues include laboratory values such as fat macroglobulenemia and serum lipid changes. Miller and colleagues (17) even proposed an autopsy diagnosis using histopathic samples. The most widely used criteria are set forth by Gurd and Wilson and require two out of three major criteria be met, or one major plus four out of five minor criteria. Major criteria include pulmonary symptoms, petechial rash, and neurological symptoms. Minor criteria include pyrexia, tachycardia, jaundice, platelet drop by >50%, elevated ESR, retinal changes, renal dysfunction, presence of urinary or sputum fat, and fat macroglobulinemia (1). Of note, none of the proposed diagnostic criteria include direct visualization of fat emboli via ultrasound or echocardiography (18-22) (Table 1).

Table 1: Gurd's Criteria for Diagnosis of FES

Gurd AR. Fat embolism: an aid to diagnosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1970;52(4):732-7. [PubMed]

Mechanism

Two theories explain the systemic symptoms seen in FES. The mechanical theory describes how intramedullary free fat is released into the venous circulation directly from the fracture site or from increased intramedullary pressure during an orthopedic procedure. The basis for the theory is that the fat particles produce mechanical obstruction. However, not all fat emboli translocated into the circulation are harmful. It is estimated that fat particles larger than 8 μm embolize (23-25). As they accumulate in the lungs, aggregates larger than 20 μm occlude the pulmonary vasculature (26). Particles 7-10 μm particles can cross pulmonary capillary beds to affect the skin, brain, and kidneys. On a larger scale, the embolized free fatty acids produce ischemia and the subsequent release of inflammatory markers (27). The mechanism of this systemic spread beyond the pulmonary capillaries is not well understood. Patients without a patent foramen ovale or proven pulmonary shunt develop FES (28). Interestingly enough, other patients with a large fat emboli burden in the pulmonary microvasculature have not progressed to FES (29). One possible explanation for this may be elevated right-sided pressures force pulmonary fat into systemic circulation (1).

The biochemical theory has also been proposed to explain the systemic organ damage. The mechanism describes that enzymatic degradation of fat particles in the blood stream brings about the release of free fatty acids (FFA) (30, 31). FFA and the toxic intermediaries then cause direct injury on the lung and other organs. The fact that many of the symptoms are seen much later than the initial injury would support the Biochemical Theory. This theory also has an obstructive component to it as it recognizes that large fat particles coalesce to obstruct pulmonary capillary beds (11).

Discussion

Fat emboli syndrome is a rare and difficult clinical diagnosis. Currently there is no diagnostic test for FES and even the reported incidence is quite variable. The wide clinical presentation of FES makes the diagnosis challenge, and classic pulmonary involvement does not always occur (31). Furthermore, the symptoms overlap with other illness such as infection, as it did in this patient who was initially thought to be septic. The delayed onset of symptoms may further confound its identification. Finally, the traditional criteria used to diagnosis FES are variable depending on which source is referenced. Case-in-point is the Lindque criteria which require the presence of a femur fracture. By this requirement the patient presented in this case would not have been diagnosed with FES as she presented with a pelvic fracture.

The patient in this case was likely suffering from undiagnosed FES from the time of her admission. Since it did not present in the classic fashion, her progressive respiratory failure and neurologic deterioration were incorrectly attributed to congestive heart failure and opioid administration.

In this patient, the diagnosis of FE was somewhat unexpected, although it was within the differential. For this case the implementation of bedside ultrasound proved critical to the correct diagnosis and subsequent outcome. Instead of following other possible diagnoses and treatment options such as sepsis in this tachycardic, hypotensive patient, supportive care was employed with the diagnosis of fat embolism in mind.

The use of ultrasound imaging is not well studied for the diagnosis of FES, however it may provide an additional tool for making this difficult diagnosis when the classic triad of rash, cardiopulmonary symptoms, and neurologic changes is not seen or is in doubt. When used to evaluate for cardiogenic causes of acute hypotension, bedside cardiac ultrasound may reveal findings suggestive of FES, as it did in this case.

Review of the literature (5-8) confirms similar echogenic findings from fat emboli as seen by TEE intraoperatively during orthopedic procedures. However, similar spheres can be seen in a number of other instances. Infusion of blood products, such as packed red blood cells, may create similar acoustic images. No blood products had been given to the patient at the time of the bedside ultrasound. Additionally cardiologists have traditionally used agitated saline to look for patent foramen ovale. This and air embolism after placement of a central venous catheter can both produce similar images. In this case the emboli were seen traveling through the inferior vena cava, inferior and distal to the right side of the heart. The right internal jugular catheter would not have showered air emboli to that location, additionally once these were seen circulating in the right ventricle, the first action performed was to ensure all ports on the central line were secure. Given that these hyperechoic spheres were present for hours, air emboli would be less likely to be the underlying etiology. The images were later seen during the formal cardiac echo, and again validated by the cardiologist as being consistent with fat emboli.

To our knowledge this is the first case report of critical care bedside echocardiography (BE), assisting with the diagnosis of fat emboli syndrome. This is in contrast to TEE which has been used to diagnose FE and presumed FES in hemodynamically unstable patients in the operating room (5-8).

BE is attractive as it requires less training than TEE and can be repeated at the bedside as the clinical picture changes. By itself BE cannot differentiate FE from FES, but since the practitioner using it is presumably familiar with the patient’s condition, it can be used to augment the diagnosis when other findings are also suggestive of FE.

It has been suggested that a basic level of expertise in bedside echocardiography can be achieved by the non-cardiologist in as little as 12 hours of didactic and hands-on teaching. Given this amount of training, the novice ultrasonographer should be able to identify severe left or right ventricular failure, pericardial effusions, regional wall motion abnormalities, gross valvular abnormalities, and volume status by assessing the size and collapsibility of the inferior vena cava (32-37). Potentially, based on this case, the list could include FE with FES in the correct clinical context, pending further clinical validation.

In conclusion, this is the first reported case of bedside ultrasonography assisting in the diagnosis of FES in the ICU. The case illustrates the diagnostic challenge of FE and FES and also highlights the potential utility of bedside ultrasonography as a diagnostic tool.

References

- Akhtar S. Fat Embolism. Anesthesiology Clinics. 2009;27:533-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gitin TA, Seidel T, Cera PJ, Glidewell OJ, Smith JL. Pulmonary microvascular fat: The significance? Critical Care Medicine. 1993;21(5):673-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza SS, Noheria A, Kesman RL. 21-year-old man with chest pain, respiratory distress, and altered mental status. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(5):e29-e32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capan LM, Miller SM, Patel KP. Fat embolism. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 1993;11:25–54.

- Shine TS, Feinglass NG, Leone BJ, Murray PM. Transesophageal echocardiography for detection of propagating, massive emboli during prosthetic hip fracture surgery. Iowa Orthop J. 2010;30:211-4. [PubMed]

- Heinrich H, Kremer P, Winter H, Wörsdorfer O, Ahnefeld FW. Transesophageal 2-dimensional echocardiography in hip endoprostheses. Anaesthesist. 1985;34(3):118-23. [PubMed]

- Pell AC, Christie J, Keating JF, Sutherland GR. The detection of fat embolism by transoesophageal echocardiography during reamed intramedullary nailing. A study of 24 patients with femoral and tibialfractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1993; 75:921-5. [PubMed]

- Christie J, Robinson CM, Pell AC, McBirnie J, Burnett R. Transcardiac echocardiography during invasive intramedullary procedures. J BoneJoint Surg Br 1995;77:450-5. [PubMed]

- Pazell JA, Peltier LF. Experience with sixty-three patients with fat embolism. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1972;135(1):77–80. [PubMed]

- Gossling HR, Pellegrini VD Jr. Fat embolism syndrome: a review of the pathophysiology and physiological basis of treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;165:68–82. [PubMed]

- Shaikh N, Parchani A, Bhat V, Kattren MA. Fat embolism syndrome: Clinical and imaging considerations: Case report and review of literature. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2008;12(1):32-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butteriss DJ, Mahad D, Soh C, Walls T, Weir D, Birchall D. Reversible cytotoxic cerebral edema incerebral fat embolism. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27(3):620-3. [PubMed]

- Nandi R, Krishna HM, Shetty N. Fat embolism syndrome presenting as sudden loss of consciousness. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2010;26(4):549-50. [Pubmed]

- Adams CB. The retinal manifestations of fat embolism. Injury. 1971;2(3):221-4. [CrossRef]

- Mellor A, Soni N. Fat embolism. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:145-54. [CrossRef]

- Bulger EM, Smith DG, Maier RV, Jurkovich GJ. Fat embolism syndrome. A 10-year review. Arch Surg. 1997;132:435-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller P, Prahlow JA. Autopsy diagnosis of fat emboli syndrome. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2011;32(3):291-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurd AR. Fat embolism: an aid to diagnosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1970;52(4):732-7. [PubMed]

- Gurd AR, Wilson RI. The fat embolism syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1974;56(3):408-16.

- Weisz GM, Rang M, Salter RB. Posttraumatic fat embolism in children: review of the literature and of experience in the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. J Trauma. 1973;13:529-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindeque BG, Schoeman HS, Dommisse GF, Boeyens MC, Vlok AL. Fat embolism and the fat embolism syndrome. A double-blind therapeutic study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1987;69(1):128-31. [PubMed]

- Schonfeld SA, Ploysongsang Y, DiLisio R, Crissman JD, Miller E, Hammerschmidt DE, Jacob HS. Fat embolism prophylaxis with corticosteroids. A prospective study in high-risk patients. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:438-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pell AC, Hughes D, Keating J, Christie J, Busuttil A, Sutherland GR. Fulminating fat embolism syndrome caused by paradoxical embolism through a patent foramen ovale. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:926-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argenziano M. The incidental finding of a patent foramen ovale during cardiac surgery: should it always be repaired? Anesth Analg. 2007;105:611-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emson HE. Fat embolism studied in 100 patients dying after injury. J Clin Pathol. 1958;11(1):28-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batra P. The fat embolism syndrome. J Thorac Imaging. 1987;2(3):12–17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer N, Pennington WT, Dewitt D, Schmeling GJ. Isolated cerebral fat emboli syndrome in multiply injured patients: a review of three casesand the literature. J Trauma. 2007;63:1395-1402. [PubMed]

- Nijsten MW, Hamer JP, ten Duis HJ, Posma JL. Fat embolism and patent foramen ovale [letter]. Lancet 1989;1(8649):1271. [CrossRef]

- Aoki N, Soma K, Shindo M, Kurosawa T, Ohwada T. Evaluation of potential fat emboli during placement of intramedullary nails after orthopedic fractures. Chest. 1998;113(1):178-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot M, Schemitsch EH. Fat embolism syndrome: history, definition, epidemiology. Injury. 2006;37S:S3-S7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy D. The fat embolism syndrome. A review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;261:281-6. [PubMed]

- Vignon P, Mücke F, Bellec F, Marin B, Croce J, Brouqui T, Palobart C, Senges P, Truffy C, Wachmann A, Dugard A, Amiel JB. Basic critical care echocardiography: Validation of a curriculum dedicated to noncardiologist residents. Crit Care Med. Apr 2011;39(4):636-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignon P, Dugard A, Abraham J, Belcour D, Gondran G, Pepino F, Marin B, François B, Gastinne H. Focused training for goal-oriented hand-held echocardiography performed by noncardiologist residents in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(10):1795-99. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manasia AR, Nagaraj HM, Kodali RB, Croft LB, Oropello JM, Kohli-Seth R, Leibowitz AB, DelGiudice R, Hufanda JF, Benjamin E, Goldman ME. Feasibility and potential clinical utility of goal-directed transthoracic echocardiography performed by noncardiologist intensivists using a small hand-carried device (SonoHeart) in critically ill patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2005;19(2):155-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melamed R, Sprenkle MD, Ulstad VK, Herzog CA, Leatherman JW. Assessment of left ventricular function by intensivists using hand-held echocardiography. Chest. Jun 2009;135(6):1416-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignon P, Chastagner C, François B, Martaillé JF, Normand S, Bonnivard M, Gastinne H. Diagnostic ability of hand-held echocardiography in ventilated critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2003;7(5):R84-91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo PH, Beaulieu Y, Doelken P, Feller-Kopman D, Harrod C, Kaplan A, Oropello J, Vieillard-Baron A, Axler O, Lichtenstein D, Maury E, Slama M, Vignon P. American College of Chest Physicians/La Societe de Reanimation de Langue Francaise statement on competence in critical care ultrasonography. Chest. 2009;135(4):1050-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Reference as: Summerfield DT, Cawcutt K, Van Demark R, Ritter MJ. Fat embolism syndrome: improved diagnosis through the use of bedside echocardiography. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2013;7(4):255-64. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc109-13 PDF

Ultrasound for Critical Care Physicians: Connecting Disparate Symptoms

An 18-year-old woman was recently diagnosed with non-ACTH-Mediated Cushing syndrome, now with a complaint of mild shortness of breath.

Her cardiac exam showed normal sinus rhythm at 84 beats per minute and blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg. Her mitral first heart sound was slightly accentuated, but the pulmonic sound was normal. Grade-I diastolic murmur was heard over the mitral area. Opening snap was absent. Lungs were clear and chest radiograph showed slight cardiomegaly. She had multiple freckles on his face and trunk and along the vermillion border of the lips.

An ultrasound of the heart was performed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Four chamber view of the heart.

Which of the following is the likely diagnosis?

- Brugada syndrome

- Carney syndrome

- Gotway syndrome

- Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

Reference as: Gotway MB. Ultrasound for critical care physicians: connecting disparate symptoms. Southwest J Pulm Crit Care. 2013;7(3):176-8. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13175/swjpcc122-13 PDF